Chinese laborers in the Old West - Coolie labor or Heroic pioneers?

The first large contingent of Chinese laborers came to California to mine gold in 1849 having been contracted by an Englishman in Shanghai.

Greetings. Thanks for coming back for your weekly Asian Studies fix.

After a hiatus, I am returning to Chinese in the California Gold Rush of the mid-nineteenth century, a fascinating subject. Not too long ago, editor, podcaster, and fellow writer and fellow skeptic Ben Radford 1 sent me a nice email saying that while he liked this column, perhaps I should return to writing books as well. Interesting, as when I started this my plan was to soon scrape together a lot of stuff on the tong wars of the old west and put it in a book, the original idea being to simply expand the history section of Tongs, Gangs, and Triads, my 1995 book, but instead every time I start to dig into something I uncover something new and eye-opening. And it’s not just minor stuff either. It’s often paradigm shifting, new interpretation of the facts stuff. (Like the 1854 and 1856 “Tong Wars” did not involve any tongs at all. See the link in the footnoes) And part of that is the issue of when the Chinese came to the old American west and searched for gold and built the railroads and opened the restaurants and laundries and so on, did these men arrive of their own free will as independent adventurers and immigrants seeking new homes or were they contracted labor without the freedom to make their own choices and decisions sent by someone else and under their control? As for the Chinese women who came to the USA during this time, I wrote about them previously, and almost none of them, sadly. came to the USA of their own free will. 2

Today’s offering is free, but the plan is to mix in content for paid-subscribers only with the free content from now on. Please consider a paid subscription, and if that is a problem for you reach out to me. I definitely want people to keep reading.

In other news, things have been very busy and distracting here lately. My writing for JEMS.com (Journal of Emergency Medical Services) is taking a lot of time this month, and in two weeks there is the FDNY Search and Rescue Conference in New York City, a four-day educational event, and I will be attending as both a participant and journalist. 3 They say there will be participants there from all over the country and the world, including Taiwan and South Korea. I am pushing for the chance to interview them and will share it here if I do.

As for politics and current events, that’s on Tuesdays, and I will indeed write something about it, but I will only share it here on Tuesdays. Read it if you want, and consider reading my book on Trump, easily available at Amazon.com. 4

As always, thanks for stopping by and we hope you will continue to read Mostly Asian History. Please feel free to share and leave contents. I very much would like to see more people read my writings here.

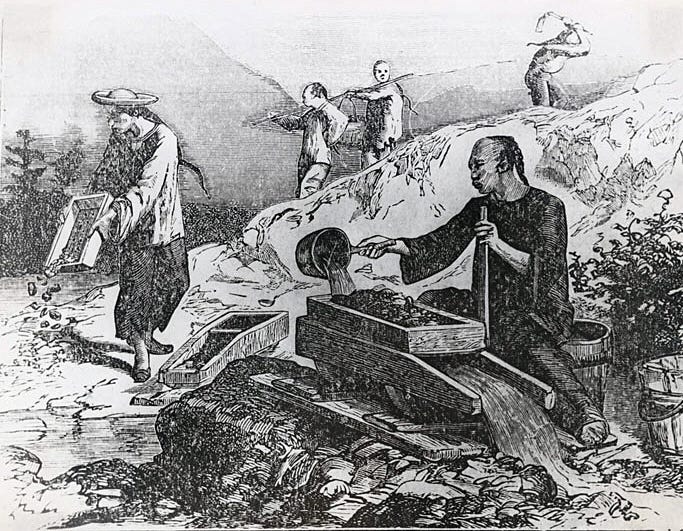

An illustration from 1905 of Chinese gold miners in the old west created by photographer Roy D. Graves, Source Wikimedia but widely available,

The world is big, we are small, much of the universe around us too large and complex to easily grasp, and part of being human is to form a construction of the world that works for us. And part of being a historian is forming a useful construct of the world, or part of the world, in the past. And different people will form different constructions with different interpretations. Often these interpretations are shaped by emotional needs or attachment to a particular ideology of some kind or another, and the result is a mythologized picture of the past. Often trying to reconcile these different descriptions or sort them out leads to fascinating discussions.

And the history of Chinese and Chinese-Americans in the Old West and during the California Gold Rush is no exception.

And one of the most widely divergent topics in this history is whether the Chinese laborers who came to the USA seeking gold in the early years or building the railroads came as lone entrepreneurs or pioneers, arriving independently and free to seek their own way in this strange new, foreign land, or if they came as contract labor, “Coolies” if you will, 5 under the control and command of someone else, someone who generally but not always was Chinese as well and usually of the merchant class. (Today’s example is one of the rare examples involving non-Chinese contractors.)

So were these Chinese laborers in the Old American West and the Gold Rush there as contract labor or independent entrepreneurs? Some of both. It’s not an easy question, which is exactly why it is so important to try and understand it. And I plan to explore it from time to time in this column and see where it goes. Today I do that by sharing what I know about the first large scale use of contract Chinese labor in the US and its territories. It’s an obscure event and not well documented but well worth writing about.

The First Large Scale Use of Chinese Contract Labor in the Old American West

The first use of Chinese contract labor shipped directly from China to perform work for hire in the USA occurred in 1849, surprisingly early, during the very start of the California gold rush. Interestingly enough, the group were recruited (I think), contracted, and shipped from Shanghai, which is located about halfway down on the east coast of China, not Hong Kong or Guangzhou which are both on the south China coast. (at least the idea originated in Shanghai) However, like Hong Kong at the time, Shanghai was seen by the Chinese Imperial government, like Hong Kong, as an unimportant place where no Chinese of much importance lived despite the increasing, expanding, and very annoying presence of foreign people of European descent settling and doing business on China’s coast.

Context and the Opium War of 1839 to 1842

To add some context, for centuries the Chinese government had tried to prevent or at least heavily restrict and limit foreign trade with the outside world. This was despite the fact that many people of European descent around the globe desperately wished to do business with China. Others wanted to enter China as missionaries, something China had allowed a couple centuries earlier but after an ugly break up with the Pope and his minions, had decided not to allow missionaries into China at all. 6 Yet foreigners wanted to come, they wanted to do business, and one way to do that was to sell opium. Despite laws against it, some Chinese would buy opium from illegal, outside sources, and they would pay for it with silver. Therefore, many, even the missionaries, were involved in the opium trade. Some justified the moral issues involved with the explanation that although selling opium was a bad thing, the long-term benefit to everyone involved of opening China to the outside world made it worthwhile.

Ultimately war broke out between Britain, the largest and most important nation involved in the illegal Chinese opium trade, and China itself. The war lasted from September 4, 1839 to August 29, 1842. The British forces defeated the Chinese forces in a manner that shocked the Chinese government and then imposed victory conditions on that nation.

Among these victory conditions was that Hong Kong island, at the time an unimportant place full of fishing villages and far from a major urban center, became a British colony with the dream being that the British would turn it into something that rivalled nearby Macao, the Portuques controlled city nearby on the South China coast. That was in 1842.

Another important part of the treaty at the end of the war was that five Chinese cities, Shanghai, Guangzhou ( aka Canton), Ninbo, Fuzhou, and Xiamen (aka Amoy) were all opened for foreign trade and the establishment of foreign trading offices. Again this was in 1842.

To put that in context, gold was found in California in 1848, approximately six years later, and the California Gold Rush is often described as starting in 1849, the year after the discovery of gold. Word of the discovery of gold soon spread across the Pacific to the newly established foreign enclaves in China as well as China proper.

The California Gold Rush of 1849 affects the Chinese coast

It makes sense that if the Opium War ended in 1842, that was followed by foreign merchants, adventurers, risk-takers, misfits, trouble-makers, and fortune seekers from Europe and the USA heading off to China arriving by sailing ship. And it was a long trip as China is a nation on the western side of the Pacific Ocean, which means if coming from Europe one has to sail south all the way around the cape of good hope in Africa and then east or perhaps head east and sail around Cape Horn and then west, If coming from the east coast of the USA, and almost no one lived on the west coast prior to the California gold rush, one had to sail south and around Cape Horn at the tip of South America and then north west across the Pacific It was not an easy trip, and by the time people arrived they knew a thing or two about ship travel.

But nevertheless, from 1842 onwards there were increasing numbers of Europeans and Americans who had made the trip to China to try and get rich and make their fortunes and put their mark on the world, When they heard about the California gold rush on the eastern side of the Pacific Ocean in 1849 it might, as they say “give them bad ideas.” By which I mean bad ideas that involved using the same ships that brought them there to sail eastward again across the Pacific and try to make their fortune in California. And some went seeking gold themselves, but at least one had a “better,” more complex idea.

He thought that instead of abandoning life in China and seeking one’s fortune there, BETTER YET, why not take advantage of whatever it was that they had found in China to try and give them the edge over their competitors when they arrived in California on the other side of the Pacific?

The first large scale use of Chinese contract labor in California gold mining occurred in 1849 just when the Gold Rush started.

And this did happen. Although we are not quite sure of who exactly tried to do it.

I also have no idea where the Chinese were recruited, or what sub-group of Chinese they were (Cantonese? Hakka? Could very easily be something completely different if they were recruited in Shanghai) Regardless, the idea of recruiting them originated in Shanghai with “an Englishman” whose name appears to be lost to history as near as I can figure out.

According to Mae Ngai, a Columbia University professor of Chinese American history, in 1849, in Shanghai, and hopefully I will write about the condition of Shanghai in 1849 someday in this column but there’s so much good stuff to write about, “an Englishman” contracted with a Chinese company to recruit about 50 or 60 Chinese laborers to sign a contract and obtain a ship to bring them to California where they were promised work upon arrival. 7

Professor Ngai does not share this Englishman’s name, and it appears his name has been lost to history with very little documented about this project as her footnotes don’t indicate great leads for further research either and my internet affairs did not find much either.

What we do know is that this “Englishman” contracted with a local Chinese firm called “Tseang Sing” or ( 祥胜行 ( This would be pronounced “xiang sheng” in modern Mandarin, and while I fully admit I am not sure what it means exactly, I think (key word “think/ believe/ best guess”) that it means “Tseang’s victory” or “Tseang’s success” with “Tseang” being a family name. I could be wrong. If I had more time, I would probably reach out to Mae Ngai although we have never met

The company was supposed to hire a ship and between 50 and 60 men, laborers and mechanics, to go to China and mine for gold when they got there. Each man signed a bilingual contract, they were given an advance of $125 passage money (I am not sure what sort of dollars exactly) with the promise that they would pay this back from their future wages. Professor Ngai, according to her footnotes, found a copy of this contract in the archives of the Wells Fargo, but not too much else about the expedition.

The group sailed to California on an English ship called “the Amazon” and it arrived in San Francisco, mid-October, October 15 to be exact in 1849. 8

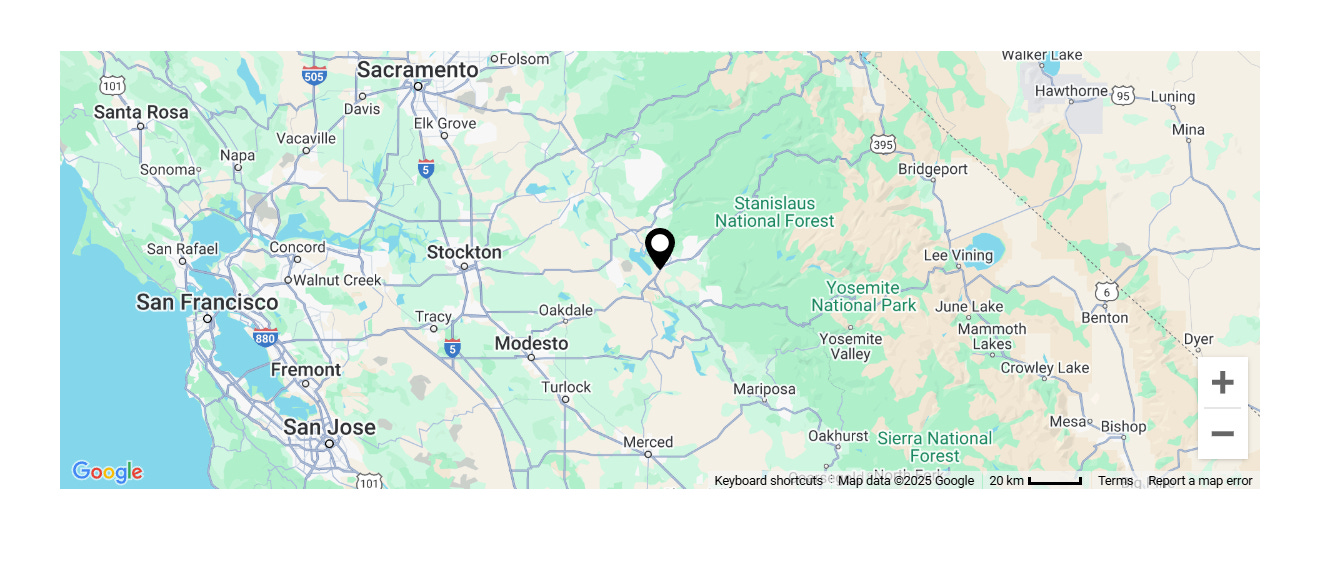

From there, according to Ngai, the group travelled to Stockton, about a hundred miles or so, and then down the San Joaquin River, and set up camp in a place called Woods Creek. south of the Stanislaus River, about 50 miles from Stockton near a group of Mexicans. (This is all according to two paragraphs on page 21 of Ngai’s book. ) This appears to be in Tuolumne County which was one of the big sites of Gold Rush activity and home to the town of Chinese Camp where the 1856 fighting took place seven years later. See my previous piece, one in a long series, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuolumne_County,_California Calaveras County,, California was another site of much gold rush activity.

I believe they went here to this location. There is a Woods Creek California Campground but its location does not fit anything described here. This location seems to be in modern Jamestown CA, a historic California Gold Rush site. 9 Note that I am not endorsing this tourist destination as I know very little one way or the other about them. Source https://www.gold-panning-california.com/woods-creek-history.html

As the group, which Ngai describes as “the English-Chinese Company,” knew knew very little about gold-mining they hired a Sonoran to teach and supervise them and soon got to work.

According to Ngai:

Other Chinese arrived around the same time in groups large and small, especially in Calaveras and Tuolumne counties. Soon there were five hundred Chinese in California, with miners making up two-thirds of the total. The Chinese dubbed “Ka-la-fo-ne-a” Jinshan (Gam Saam in Cantonese) or “Gold Mountain.” 10

And now you know just as much about the subject as I do. Perhaps it is quite possible that you know everything possible that there is to know about this expedition and all the rest that one would wish to know is lost to history.

Further Reading

While writing this I stumbled across an interesting collection of on-line diaries of California Gold Rush diaries. Alas, I do not have time to explore it at depth before deadline, but here they are. I did not see any Chinese diaries.

California Gold Rush: True Tales Of The Forty-niners

SHAMELESS SELF PROMOTION

Bizarrely enough, today I learned that the The Maritime Heritage Project ~ San Francisco has been recommending that people read my book from 1995, “Tongs, Gangs, and Triads.” See:The Maritime Heritage Project ~ San Francisco. Well that’s very flattering to say the least.

Footnotes

Ben Radford and his co-host Cecelia Ward invited me as a guest once on their “Squaring the Strange” podcast. See Dim Mak, the Kung Fu Death Touch and the Squaring the Strange Podcast

I wrote about this here last year https://peterhuston.substack.com/p/bonus-fdny-search-and-rescue-conference and later here https://www.jems.com/news/fdny-search-and-rescue-field-medicine-symposium/

Believe it or not. I am scheduled to participate in a two day training class to obtain certification in TECC or Tactical Emergency Critical Care which is basically a two day course on how to function as an EMT or Paramedic or other medical first responder in an environment where people are shooting at people. I’ve had the basics before, but this will be much more in depth. The course will be taught at least in part by members of the FDNY and NYPD special operations teams (both the fire and police department have special operations teams trained to respond to situations where there is gunfire or an active shooter.) I am looking forward to it, believe it or not, although it is a little scary to learn about what to do when people are shooting at you, but I hope to do some reading on the subject before I attend and that takes time.

Amazon link for my Trump book: https://www.amazon.com/Scams-Great-Beyond-Presidential-Paranormal/dp/B08JVPHMD1

Sooner or later, I am going to have to write a piece on the complex history and meaning of the word “coolie.” However, for the moment, it’s enough to say that in many British sources from the nineteenth century, if you run across a reference to “coolie labor” or “coolies” they are referring to low paid, hard working laborers and load bearers from India, not China. However, in this case, I am referring to Chinese laborers who were recruited from mostly impoverished and / or desperate people and who were willing to sign up for harsh contracts under difficult conditions for extended periods of time knowing up front that while they would make some money, most of the profits from whatever they did would be kept by someone else.

Again, another subject for another day perhaps, but the basic issue was whether or not Chinese Catholic converts should be leaving offerings to their ancestors and was this compatible with Catholic teachings.

Ngai, page 21. fn p 325

Ngai, p. 21.

Have you read Matthew Boroson's "The Girl With Ghost Eyes" and " The Girl With No Face"?