Chinese in the US Civil War. Part Two. "John Fouenty." Confederate soldier and Survivor of the horrible Cuban Coolie trafficking.

And the 19th Century Coolie Trade to Cuba

Greetings, welcome back. Thanks for stopping by for your weekly Asian Studies fix.

There are some new subscribers here so a quick introduction is warranted. First, this is a reader supported publication. That means any money I make from it comes from the readers. My main focus is a weekly essay, release Sundays at 5pm EST. At the moment, paid subscribers can read these when they are released. Free subscribers can read a preview and the whole thing is available to them 10 days later.

While originally, this was a politics-free, “no Trump zone,” as I am an American citizen who fears for the future of this great democracy, Tuesday is the day I try to share my thoughts and insights on ALL THIS STUFF THAT IS HAPPENING AROUND US - but it’s clearly labelled POLITICS so it’s up to you if you read it or not. Share it if you can and think it’s worth reading.

Thursdays, usually I sent a shorter smaller piece. Traditionally free, I may start charging for them.

This week, I return to Chinese in the US Civil War, and the life of a young, Chinese Confederate Civil War veteran who was called “John Fouenty” by the 1864 New York Times. This young man had been a forced laborer in Cuba for several years before becoming a Confederate soldier, a bit ironic as he was probably a former slave himself, so I am also writing about the 19th Century so-called “Coolie Laborers” who were sent to work in the hot Cuban Sun, usually on sugar can plantations, often against their will. Horrible but interesting stuff. This is my second column where I discuss young Chinese who somehow found themselves in the USA during the Civil War. ( see Misplaced Chinese Children in the 19th Century USA, May 25, 2025 and Chinese Adoptees in the US Civil War. Part One. And other kinds of Chinese or Chinese-Americans too., June 1, 2025 ) If all goes to plan, it won’t be the last.

Peace. Thanks for stopping by.

a Chinese laborer in “the West Indies” during the time of the US Civil War. This was where “John Fouenty” reportedly spent much of his childhood before escaping and becoming a Confederate soldier for a year then heading up north to New York City to escape the draft.

The Church Missionary Gleaner, 1864, page 13

Trigger Warning - Use of the Potentially Offensive word “coolie” in historical context to describe the use of low paid or sometimes unpaid Chinese contract labor in the 19th Century and Discusses Children in difficult circumstances. Oh yeah, and there’s a war in here too. I almost forgot. That’s pretty terrible too. History, you know. And a refernce to cigar smoking, as well.

John Fouenty, Confederate volunteer, later draft dodger, human trafficking victim, and New York City Resident.

When one digs into history, and start looking at lives of individual people, what you find is often fascinating in its images and hints at broader patterns yet also frustratingly limited in detail. This is especially true when you look at the lives of marginalized people, such as the person the New York Times referred to as “John Fouenty” in a New York Times piece from March 12, 1864.

According to the newspaper article, this young man, was then approximately 13 years old and had already seen more hardship and human suffering than most of us will see in our entire lives.

We don’t even know his real name and any attempts to determine his name are based on very limited information. While his birth name could not possibly have been “John Fouenty,” I have to wonder was “John” was a mangling of his surname ( our “last name”) , not his given ( our “first name”). Could it be 張 or 蔣 or what? We have no way of knowing, and no way to even know if it is, in fact, a surname at all. It could be part of his given name, or just a nickname he picked up somewhere in his strange life. We just don’t know.

“John Fouenty” was a victim of the Chinese coolie trade who was shipped to Cuba, reportedly at age seven, reportedly in the year 1851. He, like many of the other Chinese who found themselves in California, especially the women, was a human trafficking victim.

Somehow, reportedly at age seven, he had become a human trafficking victim and was shipped to Cuba from his home in China as a coolie laborer. (the New York Times article says “Hong Kong” but I question that detail. I also question the part about him being from a well to do family although I am willing to believe he said that.)

As Lynn Pan, author of the popular book, “Sons of the Yellow Emperor,” wrote, “It was a very unlucky coolie who found himself transported to Cuba.” 1 Laboring in the hot Cuban sun on a sugar plantation with poor housing, food, medical care, and stripped of basic human dignity was a horrible experience and a large number of these laborers died there instead of going home.

But this young man somehow survived. Perhaps due to his age he had been assigned alternate duties? According to Pan, “Nine out of ten coolies ended up in sugar plantations; others were sent to work on farms or coffee estates; in sugar warehouses and gas works; in bricklayers or washing establishments; on railways; on board cargo boats; in bakeries or cigar, shoe, hat, carpenters’, stone-cutters’ and other shops; as domestics or as municipal scavengers.” She then goes on to describe the terrible conditions and the use of whips and isolation to control the workers, and unripe bananas being the primary food these people were fed. 2

If half of what Pan says is true, and most likely all of it is, then it is astonishing that this child survived and left with money to even attempt to buy passage home, but that is what the historical records says he reported. After a few years in Cuba, he attempted to return home to China in 1862 but wound up in St. Petersburg, Florida instead.

And from there he wound up in Savannah, Georgia, became a cigar maker, enlisted in the Confederate forces for a years, and then fearing being drafted back into the Confederate army, he escaped and headed north to New York City.

Sadly, as far as I know, there is no way to know what happened to “John Fouenty” following this New York Times article. Hopefully he found a way to have a good lie in New York City or elsewhere, perhaps he did find a way to get back to his Chinese home. We just don’t know. And that, sadly, is part o studying history.

The full story is in the New York Times piece shared in full below. Following the story there is background on the Coolie trade to Cuba.

Historical Background of the Cuban Chinese Coolie Trade

At this time, while the Chinese government officially prohibited Chinese to go abroad except on official business or with explicit government authorization, this was widely ignored. This edict prohibiting going abroad lasted from 1644- to 1893. 3

Nevertheless, huge numbers of Chinese went abroad as the law was widely ignored and definitely not uniformly enforced.

The so-called “Coolies,” coolie actually being a word of Indian, not Chinese origin, were recruited by people called “Crimps.” Some Crimps were Chinese, many were not. They came from a variety of nations from around the world. Deceit, treachery, kidnapping, and rigged gambling games were all means used to obtain “Coolies,” as was purchasing of enslaved Chinese people who were usually purchased from other Chinese people. The Crimps would imprison them, and catalog them.

Wang offers this description from John Bowring of what he saw in Amoy (modern Fujian. Fujian, by the way, is still the primary source of overseas Chinese laborers in the USA. Next time you are in a Chinese restaurant in the USA, ask the staff if they are from Fujian or not).

Hundreds of them gathered together in barracoons, 4 stripped naked, and stamped or painted with leters “C” (California), “P” (Peru), and “S” (Sandwich Island) on their breasts according to the destination for which they were intended. 5

After storage sorting of the human laborers, the persons who had the coolie labor contract would get them on the ship and en route to their destination before they could escape, And while many died on these ships, enough survived to ensure profit for the people who arranged the contracts. 6

Interestingly enough in the context of him fighting in a major conflict over slavery, the entire “Chinese coolie trade” was begun in response to the end of slavery in the British Empire in the year 1833. 7

There were however many industries throughout the British Empire, and the world at large, that were dependent on very low cost human labor to survive and thrive. To meet this need brokers were found, some with experience with the slave trade, and men were recruited or tricked into being sent to far away locations for extended periods of time as low cost labor.

While destinations varied, the source below say:

According to Yun & Laremont (2001), “coolie labor was utilized in Cuba, Peru, Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica, Panama, Mexico, Brazil, and Costa Rica, among other places in the Americas.” (p. 101). There was also demand for coolie labor in Chile, the West Indies, California and Australia (Farley, 1968). 8

As for Cuba, the place where “John Fouenty’ went for several years:

The Cubans — Between 1847-1874, between 125,000 and 150,000 Chinese indentured or contract laborers, almost all male, were sent to Cuba (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p. 67; Yun & Laremont, 2001). The major player in starting up the Chinese coolie trade in Cuba, where coolies were needed to grow Cuban sugar production on plantations, was a company called Real Junta de Fomento y Colonización (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Real Juanita partnered with the company Julieta y Cia in London, England, which was run by cousins Julián Zulueta [0012023] and Pedro Zulueta (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Together, these companies schemed to transport Chinese men to Cuba and sell the men. More specifically, they sold each man’s contract, as opposed to the man himself, to Cuban plantation owners. They relied on Pedro Zulueta’s experience as a successful African slave trader to help them create efficient processes. The Zulueta cousins found labor agents in Asia (Fernando Aguirre in Manila and a Mr. Tait based in Amoy/Xiamen) and contracted their companies to get the first shipment of coolies from China to Havana, Cuba (Yun & Laremont, 2001). 9

While slavery was actually legal in Cuba at this time, there was a demand for “coolie labor” as the number of enslaved people was not sufficient to keep up with the labor needs of the Cuban sugar cane plantations.

In 1874, ten years after the newspaper story about “John Fouenty,” things reached a point where the Chinese government sent an official commission of enquiry to Havana to determine the truth behind the horrific reports they had been receiving.

The investigators were assembled from people from several nations. (See below). According to Pan, four fifths of those interviewed said they had been kidnapped, herded like cattle by “foreign men with whips,” then held at quarantine stations where their queues, their long pony tail, was cut -an act of humiliation and bodily violation for a Chinese man of this time, and then stripped naked and sold to prospective buyers who had the right to examine their bodes prior to purchase (technically, it was not them but their contracts that were sold, but the effect is the same if one is being stipped naked by strangers who intend on forcing you do things you do not wish to do after handing money over to agents of the people who kidnapped or tricked you..)

According to Ng, the Chinese investigation revealed that almost 90% of the Chinese people sent to Cuba who they interviewed told them that they had been sent to Cuba without their consent. The investigation also learned that at the end of the contract, the coolies were not released as promised but generally forced to continue laboring. At this point, many commited suicide and ultimately less than 2% of them made it home. 10

In 1876, the Chinese published their report and ultimately the Spanish government freed 43,298 of the approximately 126,000 Chinese Coolies who had come to Cuba between 1847 and 1877. 11 As for the others, Pan states they had all died, but, if “John Fouenty” is to be believed, we do know that at least some of them finished their contractual period and were allowed to leave, although Pan makes it clear that many were not. Perhaps, due to his young age, and an apparent ability to charm people that helped him in St Petersburg and in New York City, he was given special treatment. Speaking as someone who has worked with refugees, having the ability to get people to like you, is a much under-rated survival skill.

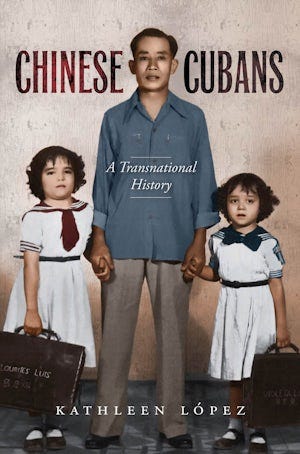

And now a plug for a book I have never read.

Perhaps this is here to reinforce the basic concept that the world is a much bigger, much more complex place than most of us can imagine, and history and the social sciences cover things in depth that most people don’t even know exist, but honestly, i just like the picture.

As stated, I have not read this but wish I could. Here’s the blurb”

Awards & distinctions2014 Gordon K. and Sybil Lewis Prize, Caribbean Studies Association

Special Mention, 2015 Elsa Goveia Book Prize, Association of Caribbean Historians

In the mid-nineteenth century, Cuba's infamous "coolie" trade brought well over 100,000 Chinese indentured laborers to its shores. Though subjected to abominable conditions, they were followed during subsequent decades by smaller numbers of merchants, craftsmen, and free migrants searching for better lives far from home. In a comprehensive, vibrant history that draws deeply on Chinese- and Spanish-language sources in both China and Cuba, Kathleen López explores the transition of the Chinese from indentured to free migrants, the formation of transnational communities, and the eventual incorporation of the Chinese into the Cuban citizenry during the first half of the twentieth century.

Chinese Cubans shows how Chinese migration, intermarriage, and assimilation are central to Cuban history and national identity during a key period of transition from slave to wage labor and from colony to nation. On a broader level, López draws out implications for issues of race, national identity, and transnational migration, especially along the Pacific rim.

More info: University of North Carolina Press --Chinese Cubans A Transnational History By Kathleen M. López

Random, Loosely Connected, Film Clip

Long time readers know I like to watch movies. Years ago, I watched the Miami Vice movie. (Interestingly the version I watched was a pirated DVD purchased in China, by the way.) While the film, a return to the iconic 1980s TV series, is in my opinion a pretty standard action movie, I only saw it once and only really plan to see it once, it does have very interesting casting if one digs deeply with very few of the actors speaking with their natural accents. One of the most interesting pieces of casting is Gong Li, one of China’s most prominent actresses of the time, 12 as the Cuban drug lord. The producers made it quite clear when asked that there were, indeed, many Chinese Cubans and it would not be impossible to find a Chinese Cuban drug lord.

The scene below does contain spoilers by the way, but it does show a Chinese actress portraying a Cuban drug lord.

Bibliography

Pan, Lynn. 1990. “Sons of the Yellow Emperor, The Story of the Overseas Chinese.” London, UK: Mandarin Paperbacks, Michelin House. (Multiple publishers available including University of Michigan.)

Wang, S.W. 1969. “The Organization of Chinese Emigration, 1848-1888, with Special Reference to Chinese Emigration to Australia.” Master’s Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra Australia. (Available on-line.)

Footnotes and

Page 68. Pan, Lynn.

Page 67-68, Pan, Lyn.

Wang, S.W. page 18

Quoted in Wang, S.W. page 64.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Bowring

Wang, S.W. and Pan and Macao to Havana and Beyond: The Chinese-Cuban Coolie Trade - Indentured Labor (or Pseudo-Slavery) from 1847-1874 Posted by Jessica Katz on November all discuss this. Wang has several pages, pages 51 to 58, on this.

Pan. Page 69.