Chinese Adoptees in the US Civil War. Part One.

And other kinds of Chinese or Chinese-Americans too.

Thanks for coming back for your weekly Asian Studies fix. Should you be new here, each Sunday I publish an original essay on Chinese, Chinese American, or Asian history or culture. While a major area of interest lately has been the way the California gold rush not only brought Chinese to California and the American West, but also how the gold rush affected events in Asia on the other side of the Pacific, I do try and mix things up.

A recurring theme here is that I find a subject, discover more and more fascinating, interesting, and insightful stuff, and it becomes the topic a few different columns. And this is happening with the two most recent subjects, Chinese language newspapers of mid-19th Century California during the gold rush era, a completely new subject to me, and Chinese adoptees who served in the US Civil War. Expect several pieces on these subjects over the next few weeks, but other topics should appear too.

While originally this column was politics free, a “no-Trump” zone, events of the last few months here in the USA disturb me greatly, and I have been adding in a POLITICS column on most Tuesdays. Sometimes on Thursdays I add a shorter piece where I share something I found on the internet relating to Asian culture or history.

This is a reader supported publication which means the only money I get comes from paid subscriptions although I do want as many people as possible, paying and non-paying, to read it. Currently I am sharing a preview to non-paying subscribers and then resending the full essay to non-paying readers 10 days later.

As always, thanks for stopping by and checking this out.

[Corporal Joseph Pierce of Co. F, 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment in uniform] / W. Hunt, photographer, 332 Chapel St., New Haven, Conn. Born in Guangzhou (Canton), China 1842. 1

The American Civil War lasted from 1861-1865, beginning 12 years or so after the discovery of gold in California. It was a cataclysmic event. Huge numbers of American from all walks of life fought in the war and countless civilians died or had their lives changed or touched by it as well.

And among them were a very small but interesting number of Chinese who fought in the American Civil War as well. Many of these had been brought to the US and basically adopted or cared for by White American families. While we focus on these, they were only one part of the Chinese and Chinese Americans who fought in the US Civil War.

Chinese and Chinese Americans in the US Civil War

The Chinese who fought in the war basically fell into three categories.

* Those who were born here.

Since there were almost no Chinese in the USA before the gold rush, there were very few Chinese or Chinese descended people of suitable age who had been born in the USA and were old enough to fight 12 years later when the Civil War erupted.

While there may very well be others, arguably the only two I know of were two sons of Chang and Eng Bunker, the famed performing “Siamese Twins” of the early 19th Century. 2 Although Chang and Eng were from Thailand, then known as Siam, hence the term “Siamese twins,” they were of Chinese descent as Thailand has had a large overseas Chinese community for centuries. They were brought to the USA by a Scotsman, and performed in circuses and so-called “freak shows” 3 from the years 1829-1839, including a tour of Europe, and gained a great deal of wealth and fame in the process. In fact, it is due entirely to their fame that today conjoined twins are often referred to as “Siamese Twins,” although many find the term offensive today. Along the way, they adopted the last name “Bunker” after they met a kindly woman named “Bunker.” After leaving performing, the two brothers bought a slave plantation in the south, Mount Airy Plantation in North Carolina, owned over 30 enslaved people of African descent, married two southern American women of European descent, and had 21 children between them. Two of these children, Christopher Wren Bunker 4 and Stephen Decatur Bunker 5 served in the 37th Battalion, of the Virginia Cavalry. One was wounded in the war, the other captured.

This family portrait from the 1860s shows Chang and Eng Bunker with their wives and 18 of their 22 children. It also includes Grace Gates, one of the 33 enslaved people on their plantation. 6

While there may very well be other Chinese American Civil War Veterans who were born in the USA, I am not aware of them.

* Those who came here as adults from China shortly before or during the war and then enlisted to fight on one side or the other.

While there were not many of these, particularly as the war was fought mostly in the eastern half of the nation while most of the Chinese here at the time were in the Western half, they did exist, and we have some of their names and units. Well, at least something that resembles their names as there was not yet a recognized systematic approach to spelling Chinese names and thus few really had any idea of how to spell Chinese names at the time, including the Chinese themselves who had that name.

It also needs to be mentioned that most Chinese had arrived and settled on the west coast of the USA, and while the civil war included activity in California, 7 most of that activity involved sending either people or supplies, including gold, east, and while California did raise units to join the federal or Union army often these units were assigned to operations against the indigenous peoples of the southwest thus freeing up troops for activities against Confederates in the East.

However, according to the Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 21, Number 3178, 4 June 1861, there was a proposal among Chinese merchants in California to raise a Chinese regiment to aid the union, but the offer was refused. See:

Source and alternate text. 8

As an aside, Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Indian who studied civil engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy NY and law through an apprenticeship, offered to raise a regiment of Iroquois to fight for the north but his offer was also turned down by the then governor of New York. Parker, however, went on to enlist himself though and became a Colonel and an aide to Ulysses S Grant, who then made Parker Commissioner of Indian Affairs, when Grant was president. 9 Therefore the Chinese were not the only non-Caucasians whose offer to raise a regiment to aid the Union was refused.

* Those who were brought here as children, were then adopted into American famiies, and then enlisted in the war just as their neighbors did.

And this is where things get really interesting. As mentioned last week, ( see Misplaced Chinese Children in the 19th Century USA Published May 25, 2025) from time to time, Americans of the time, usually sailors, merchants, or missionaries, would travel to China (or Hong Kong or Macao) and return with a child, usually an orphan or otherwise uncared for child, and raise them in the USA.

While there is little information available on these children for reasons discussed last week, one place where some do appear in the historical record is among the rolls of Civil War Veterans.

We’ll start with one illustrative example of Joseph Pierce, a well-documented, Chinese American who served in the US Civil War. I plan to write about others in future columns.

Joseph L Pierce

The life and career of Joseph L. Pierce is one of the best documented among the Chinese and Chinese Americans who served in the US Civil War.

He was born in 1842 in Guangzhou (Canton) China and while there are two versions with slightly different details of events, details such as price and whether he was sold by his father or older brother, both stories state that the boy’s family was not able to feed or care for him or for some other reason did not want him and in 1853 therefore sold him to an American ship captain named Amos Peck III.

Peck took the young man and used him as a cabin boy on his ship, where the sailors called the child “Joe.” His actual name, his Chinese name, does not seem to be recorded and seems to have been lost to history. (I could be way off her, but I wonder if it might be connected with his middle initial “L.” I have no idea what that “L” stands for or where it comes from? Could it be his Chinese name? No idea.)

Upon arrival in Connecticut, Amos Peck, a lifelong bachelor, 10 soon announced that he would soon be leaving on another voyage, as sea captains do, and therefore turned the child, referred to in some sources as “his 10 year old slave,” over to his mother for safe keeping.

According to McCunn:

When Peck, a lifelong bachelor, went home, he "handed his l0-year-old 'slave' over to his mother to rear since he was starting on another voyage. Mother Peck taught Joe how to read and cipher [and] he went to school with Amos'younger brothers and sisters in the same country school in Kensington they attended." 11

Now personally, the thought of this incident and subsequent interaction just boggles my mind. I first imagined it to go a bit like this: “Hi Ma, I’m back from China. I found this 10 year old Chinese boy for sale, and brought him home. Would you mind taking care of him for the next few years?” — or words to that effect. I don’t know. It’s kind of tough to imagine the conversation.

Which sounds a bit weird, but things got a bit weirder as I dug into it.

I went to Amos Peck III’s “find a grave” site and it gives his family members and confirms that he was a life-long bachelor who never had any documented children despite living to the age of 71 and coming from a prominent family. (He lived from Nov 14, 1794 to April 26, 1866 which indicates that he purchased Joseph at age 59.) His mother, Lois Chatterton Peck, lived from 1752–1852, and had died before he returned home from China with Joseph, indicating that the woman who took Joseph in was probably his father’s second wife, his step-mother, Lovisa Todd Peck, who lived from 1797–1865, and was actually three years younger than him. His father, Amos Peck II, 1749–1838, had been dead for over 10 years. Could his siblings, who probably had children around the same age as Joseph, been involved in the decision for the child to stay in Berlin, Connectictu?

Which just makes me wonder what happened. Did Amos Peck III ask the family to care for his newly purchased cabin boy? Or, if we assume the worst, did Amos Peck III’s family decide that it was not appropriate for Amos, life long bachelor, to be hanging out with a newly purchased 10 or 11 year old boy, and made the family look bad in front of the neighbors, and therefore insist that he turn the child over to them immediately? Or perhaps the 10 or 11 year old boy who clearly grew up in tough conditions, had learned to be charming to get his needs met and convinced the larger family and the stepmom to take him in finding their house a much nicer place to live than on a crowded ship full of sailors where he had to clean toilets and run errands all day? No idea, and no way to know these days I suspect but it’s fascinating to wonder. 12

Regardless, Peck’s stepmom and the Peck family agreed to take care of the child and seem to have done a pretty good job of it. The Peck family decided to give the child the name “Joseph Pierce,” “Joseph” coming from “Joe” and “Pierce” coming from “Franklin Pierce,” the then serving President of the USA. The Pierce family took him in and sent him to school and church along with the rest of the family.

For the record, I have not been able to find the source of the middle initial “L” or learn what it stands for, at least not yet.

As an interesting aside, people who served with Joseph Pierce during the war. reported that he told them he was found floating in the ocean offshore by a Captain Pierce, not Peck, and then brought to Connecticut. (Which kind of makes me wonder if he was trying to hide his connection with Amos Peck III from his army buddies, but, again, what do I know. No one wants to tell people their family sold them as a child, obviously, but why hide the name of the person who brought him to Connecticut?)

There don’t seem to be too many details on his school years, but on July 26, 1862, in New Britain, Connecticut, Joseph Pierce voluntarily enlisted in the Union Army to serve in the war as a soldier in Company I Fourteenth Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. He fought at the Battle of Antietam, a major battle of the war, where he fought with distinction but was badly wounded. Although he spent months convalescing and was assigned duties as a cook for a while, he was sufficiently recovered to fight at Gettysburg.

According to MCunn:

Returning to his unit in May, he distinguished himself in Gettysburg, where he was among the first to go out on the skirmish line on Julv 2 and volunteered for the critical attack against the Bliss Farm on July 3, the day of Pickett's charge. "The Bliss barn and farmhouse bordered by a l0-acre orchard- and a field of wheat,” lay roughly halfway between the Confederate and Union armies. “Because of its sound masonry construction, the barn became a miniature fortress,” and the two armies "struggled for its possession." On the morning of July 3, Confederate sharpshooters, once again in control, were firing at Union positions on Cemetery Ridge, and General Alexander Hays ordered colonel Thomas A. Smyth “to rid his troops permanently of this vexation." Smyth called upon the Fourteenth Connecticut to carry out the order, which they did under “savage fire” [thus] contributing to the great Union victory later in the afternoon.

That evening Pierce was among the men detailed to gather the Confederate wounded.

Taking from the same essay by McCunn:

Promoted to Corporal on November 1, 1863, he was assigned to “recruiting service” in the following month, and was sent back to conscript camp in New Haven from February 9 through September 1, 1864, when he returned to his company, mustering out with them at Baileys Crossroads, Virginia, on May 31, 1865. This promotion was significant as there were only three corporals and three sergeants to a company. 13

Copying more from McCunn, a woman who has done so much important research on this subject:

Pierce did not return to Berlin or to farming. Instead, he settled in Meriden, (boarding at first with a member of the Peck family), where he worked as an engraver in its famous silverware industry. A confirmed dandy with his silk hat and everything that went with it," he did not marry until November 12,1876, when he was past thirty. His bride, a Martha A. Morgan from Portland, was twenty-one. Together, they had four children-Sula on April 24,1879, Edna Bertha on January 22, 1881, Franklin on May 13, 1882, and Howard on January 2, 1884-but only the sons survived infancy. 14

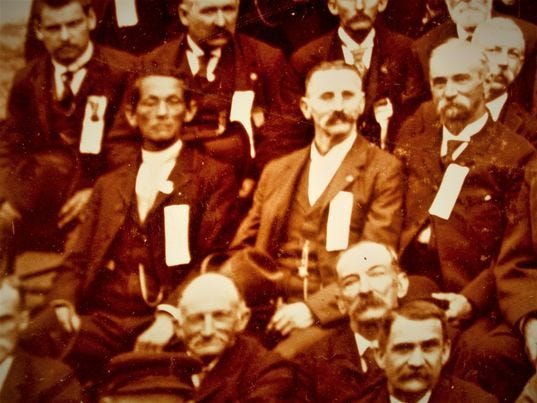

Joseph at a 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry reunion. Date Unknown. Taken from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/12918691/joseph-pierce#view-photo=279610568

Courtesy of I. Moy, a descendant of Pierce who wrote a book about him.

Although he had to struggle with the bureaucracy and paperwork, he did manage to get a veteran’s pension. He was turned down, and even had to come up with a date of birth testified to as accurate by both himself and a respected associate, before reapplying successfully for the pension. (As his date of birth did not seem to be recorded, I question the accuracy of the date of birth despite these testimonies. For the record, the date given was November 16, 1842, but, according to his Wikipedia page, yes, this man has a wikipedia page, when enlisting he gave his date of birth as May 10, 1842. 15

Also, according to Wikipedia, “The Pierce family attended the Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church in Meriden, where Pierce himself was baptized on November 6, 1892.” 16 That would make him approximately 50 years old.

His story reached the New York Times in 1899 in an article on “Chinamen” (pardon the use of this period term) who were receiving military pensions for their Civil War Service.

CHINAMEN WHO GET PENSIONS.; Ah Yu, Who Serve on the Olympia, Not the First on the Lists. Special to The New York Times. July 29, 1899

CHINAMEN WHO GET PENSIONS.; Ah Yu, Who Serve on the Olympia, Not the First on the Lists. Special to The New York Times. July 29, 1899 17

He died on January 3, 1916. He was buried in Walnut Grove Cemetery, in Meriden, Connecticut. 18

The issue of his racial classification in official records is interesting. When he enlisted, “Asian” was not an existing classification in the US military where the only categories at the time were White, Black, or “Mulatto.” Pierce was enlisted as “White” in the official records, presumably because he lived with a White family and had White neighbors and clearly was not Black. 19 However, according to his wikipedia page, “In the 1880 United States census, Pierce registered his race as "Chinese," but due to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, he listed his race as "Japanese" for the 1890 census.”

Today his face is on the “Getysburg Wall of Faces” at the visitor's center in Getrysburg National Military Park. 20

I hope to share information on the lives of other Chinese adoptees who served in the US Civil War here in the future.

Chinese and Chinese American Veterans of the US Civil War

In the last twenty years or so, McCunn and others have begun to explore the reality of Chinese-Americans who fought in the US Civil War. In 2014, in Boston, Massachusetts, I attended a talk McCunn gave on this subject given at the The Chinese Historical Society of New England (CHSNE) on the subject. 21 MCunn said that when she began her research and would reach out to the National Park Historians who worked at the Civil War battlefields, a group of people who are, by the way, generally both very well informed and quite helpful, and asked if they knew anything about Chinese or Asian-American veterans of the US Civlil War, the typical response she got was a condescending “I’m sorry, man. There weren’t any.”

When she responded with something like “Actually, I’ve already found seven of them,” the response shifted suddenly to eager curiosity and a desire from the rangers for her to share what she knew. Eventually the number of known Chinese-American Civil War veterans grew, and today some say there are 58 found so far which includes soldiers on both sides of the conflict. (I have not found the original source of this number.)

Now to add some context here’s what the National Park Services says if you would like to know the total number of Chinese and Asian American Civil War veterans.

Enlistment Strength

Enlistment strength for the Union Army is 2,672,341 which can be broken down as:

2,489,836 white soldiers

178,975 African American soldiers

3,530 Native American troops

Enlistment strength for the Confederate Army ranges from 750,000 to 1,227,890. Soldier demographics for the Confederate Army are not available due to incomplete and destroyed enlistment records. 22

So therefore, those Chinese-American Civil War soldiers, all 58 of them represent only a small drop in a very large bucket of men, 23 but the fact that they were there at all is fascinating, and how they wound up there is likely to produce some fascinating and eye opening stories.

Now in order for a Chinese or Chinese American to serve in the US Civil War, they must have been in the USA and geographically able to participate, generally felt enough of a connection to the conflict to have an interest in fighting in it, and be physically and mentally able to enlist and probably have enough English ability and ability eat American food to serve in the US or Confederate Army for an extended period of time, and then have gone and enlisted.

There weren’t too many Chinese in the USA who fit this description, but of those who did and whose life stories we are able to piece together today, a noticeable and surprising number were people who were taken to the USA from China as little children and raised by White families. What fascinates me is the question of how many other such people, the people I am referring to as “Chinese adoptees” until I find a better term, did not serve in the military and thus await completely undiscovered with no way to know how many there were.

Footnotes and References.

For an excellent book that puts this sort of show in historical context, see Bogdan, Robert ( 1988) Freak Show -Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bogdan was a Professor in the field of special education and his book contains a great deal of information on not just freak shows but how people of that day saw foreign nations and how museums and the “educational shows” of the time functioned. It needs to be noted that these sorts of shows were considered educational by the people who came to see them.

See https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SDU18610604.2.10&srpos=704&e=------186-en--20--701-byDA-txt-txIN-Company+flag----1861---

”One o'clock p. m. — The Herald says, among the candidates for Congress before the 4th of July State Convention, we hear the name of John A. McGlynn, of this city, mentioned. D. W. [Cheesman], Sub-Treasurer, has filed his bond for $400,000, and taken his office. The Typographical corps, which has been enrolling its members, is full, and will elect officers immediately. A prominent Chinese merchant was on Saturday trying to get liberty to raise a company or regiment of Chinamen, and have them mustered into service. He was refused. V.'in. Vt mverueur Morris will be a candidate for Attorney General before the Union Democratic State Convention. Murray Morrison informs the Herald that no Secession iUg was raised at El Monte, but they were forced to use the Bear flag, as they had ne other. James Murphy, with several aliases, chloroformed and robbed Nathan Shelly, on thi San Bruno turnpike yesterday. Murphy had not been arrested.”

See his grave here https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8654320/amos-peck

See page 162 of of this 32 page PDF of an essay published in a book see https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.pdf or https://web.archive.org/web/20240305092750if_/https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.

See same source. Page numbered 163 of this 32 page PDF of an essay published in a book see https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.pdf or https://web.archive.org/web/20240305092750if_/https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.

See Page 164, of this 32 page PDF of an essay published in a book see https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.pdf or https://web.archive.org/web/20240305092750if_/https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.

See https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1112&context=gcjcwe for background.

There is a surprising amount available on the life of Joseph Pierce which is why I decided to start with him.

Among the sources used and which I recommend are the folowing.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Pierce_(soldier)

Joseph Pierce: The Civil War Service of a Connecticut Chinese - New England Historical Society https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/joseph-pierce-the-civil-war-service-of-a-connecticut-chinese/

McCunn’s valuable essay is available in two different places on the web. See https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.pdf or

https://web.archive.org/web/20240305092750if_/https://www.mccunn.com/Civil-War.pdf

The National Park Service eventually published a 130 page book or booklet on the subject of Asian and Pacific Islanders in the Civil War, it’s free online, and it’s fascinating reading. See https://americasnationalparks.org/asians-and-pacific-islanders-in-the-civil-war/