Greetings, welcome back for your weekly Asian Studies fix. This week, I am back exploring the Chinese influx during the California gold rush. Eventually I expect, to wrote a book on the subject, but I am still at the stage of “I know what I know, but I don’t know how much else there is out there that I don’t know yet,” so the thought of writing a book on this subject is very intimidating to me. I am still at a point where I find myself stumbling across things I had no idea existed. For instance, last week, I wrote about the first Chinese language newspaper in North America. This week, I will be writing about the second Chinese language newspaper newspaper in North America, and the details, actually, are even more important than the first. (And to a historian, period sources and period descriptions of events are one of the greatest gifts possible.)

Like last week, there will be a pay wall in this piece, therefore please do consider a paid subscription, but the entire piece will then be resent to non-paying subscribers 10 days from now so it will be for free in about a week and a half. I’m going to experiment with this way of doing things for a while. It takes time to write this, and it takes money to purchase some of the obscure books I am purchasing, so if you want to support this project, not only would a paid subscription be nice for me, but they are on half price for you.

In other news, as stated last week, I have been pushing myself too hard and over-stretching myself. I remain committed to my weekly Sunday evening (Eastern standard time) essay column on Asian studies, Chinese, Asian, or Chinese-American history. Everything else, the political columns or the Thursday night media sharing column, are optional and will be done based on my schedule and how I feel, but they will happen sometimes, but other times they won’t. Part of this is that I am busy with my Emergency Medical Services journalism right now. ( see Pete's EMS Journalism . There were two EMS articles published last month, and two so far this month with more on the way.) Not only have other proposed writing projects been neglected, but there are several non-writing projects that deserve my time (including diet, exercise, cleaning my living space, and just plain sleeping more.) Nevertheless, I do actually have an interesting piece already in the pipeline for this Thursday, but it won’t always happen.

Stay tuned, but thanks as always for stopping by. And now for the amazing story of the USA’s second Chinese language newspaper.

Tung Ngai San Luk ( 東涯新錄 )

or "The Oriental."

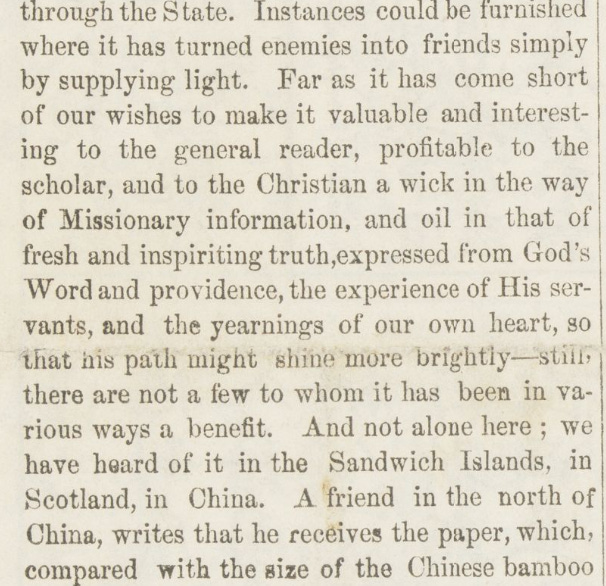

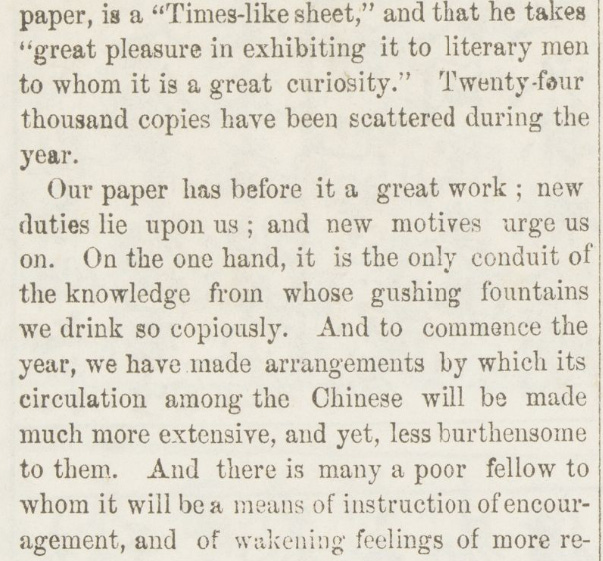

Editorial from The Oriental, Vol. 2, No 1, January 1856, San Francisco, USA. (English edition, of course)

As is customary, editorials are not normally signed, but I suspect William Speer wrote this.

For some context, the references in the first paragraph to “their companies, their numbers, and coolies” was to three of the common concerns about the Chinese that their Euro-American neighbors held. In order, “their companies” was the concern that Chinese organizations had a quasi-governmental, undemocratic control over the Chinese laborers that was outside of American law, “their numbers” referred to the fear that the number of Chinese was more than the USA could easily assimilate or use benefically, and “coolies” refers to the concern that some of the Chinese laborers who came were basically slave or very low priced contract labor being exploited in a non-democratic fashion by other Chinese. These fears were widespread and if you read The Oriental, the publisher, William Speer, often wrote against these fears in its pages and then reprinted the same pieces and spread them as far as he could. While I find some of his writings on these subjects appear a bit naive to me at times, I admire him for speaking out and working against racial prejudice and the legislative and personal injustices that the Chinese experienced in this place and time.

But The Oriental wasn’t entirely devoted to religious matters. For instance, this is from the same edition and wrote of how Californians could benefit from perhaps learning more about Chinese institutions.

If you wish to read the article in full, two English language editions of this paper can be found here, https://delivery.library.ca.gov:8443/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE326066&fbclid=IwY2xjawKW8YlleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETE3bVdLcXJwdW1Sb3VNUkhZAR6a6LX4pa9JeGtmnvS_0UTuLn6Dw3kxk0v57hSS7xO7dSIz4RJqC-Q6wNCd9w_aem_CSmvhykCQZA99j4zeiLy_g , courtesy of the California State Library.

Although the quality is not as good, the entire two years of the paper can be found online here, at Archive.org, both Chinese and English language versions. It’s fascinating reading and browsing: https://archive.org/details/per_tung-ngai-san-luk_tung-ngai-san-luk_january-1855-december-1856_ia40330207-26/page/n93/mode/2up

The USA’s second Chinese language newspaper, like the first, was published in the San Francisco area by American missionaries during the gold rush era. Unlike the first, however, it was bilingual. Therefore, its intent was not just to reach out to the Chinese in their own language, but also to reach out to the English speaking residents of San Francisco in their own language too. Many of these English language articles were intended to explain Chinese culture and the lifestyle, culture, and community practices and institutions of the Chinese to their non-Chinese, non-Asian neighbors and fellow California residents, the majority of whom, like the Chinese, were relative newcomers to the state and region. While its predecessor lasted only three months, this one lasted two years. Its longevity and accessibility make it a treasure to people researching this fascinating period of world history.

For those who wonder, the USA’s third Chinese language newspaper emerged in Sacramento in December of 1856. Called “Chinese Daily News” or 《沙架免度新錄》. “沙架免度” is an old way to write “Sacramento” in Chinese ( pronounced 《saa1 gaa3 min5dou6》in Cantonese) and “新录” means “New Record.” Unlike the other two papers, this one emerged among the Chinese themselves (although the editor was a graduate of a missionary school) and I hope to bring you the story on that in a future column. After that, as near as I can determine, there seems to have been no Chinese language newspapers in the USA for almost 20 years strangely enough.

But as for the Tung Ngai San Luk ( 東涯新錄 ) or "The Orientalist," where it did it come from and who were the people behind it?

The USA’s second Chinese Language newspaper, Tung Ngai San Luk

Let’s begin with a good general introduction to this publication taken from The American Antiquarian website:

The Oriental, or, Tung-Ngai San-Luk · The News Media and the Making of America, 1730-1865

Description

Newspapers in foreign languages catering to the growing immigrant populations popped up throughout the antebellum era. They appeared in German, French, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Welsh, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Dutch, and Hawaiian.

Chinese newspapers were also periodically published, but the character-based rather than letter-based language proved particularly challenging to printers. Whereas all of the other languages listed above could use common letterpress type, the same would not work for Chinese, with its thousands of characters. The solution for early Chinese papers was lithography, which used grease pencils on special stones to print instead of individual pieces of type.

Seen here is the second Chinese-language newspaper established in the United States, The Oriental; or, Tung-Ngai San-Luk, first published in January 4, 1855, and edited by the Reverend William Speer (1822-1904), a Presbyterian minister. Though its publication schedule was often inconsistent, it was initially intended to be published triweekly in Chinese and weekly in English. This was later changed to weekly in Chinese, monthly in English. It lasted just two years, folding in 1857. (The first Chinese-language newspaper, the Chin Shan Jih Hsin Ju; or, Golden Hill’s News, published in San Francisco in 1854, lasted for only a few months.) No Chinese newspapers were attempted again until the 1870s when a number of titles began in San Francisco.

The Reverend William Speer

It was a project of the Reverend William Speer, a Presbyterian Missionary who received medical training 1 and then went to Guangzhou (Canton) from 1847 to 1850 where he learned Cantonese . In 1850, he returned to the USA due to medical issues. In 1852, the Presbyterian Church sent him to San Francisco to work with the newly arrived Chinese.

As an aside, it’s easy to forget that the “newly arrived Chinese” were not the only newly arrived people in the region during the gold rush era. Almost everyone, except a small number of Mexicans, some indigenous Native American Indians, and a handful of Whites, had arrived about the same time the Chinese began arriving in California and for the same reason. Gold had been found! All those newly arrived Americans, Chileans, Australians, and others were new too, not just the Chinese. Prior to the gold rush, San Francisco was basically a village with less than 500 people.)

William Speer was quite concerned with the situation of the Chinese, their future and their treatment in California, the possibility of bringing Christianity to China, and the future of Chinese-American or Sino-American relations. This publication included many pieces trying to bridge the culture gap and urge everyone to get along better. He is a fascinating historical figure, both widely travelled and widely published, and its well worth reading his wikipedia bio. 2

Lee Kan ( 李根), Chinese language editor for both Kim-Shan Jit San-Luk (金山日新录) AKA “The Golden Hills News” and Tung Ngai San Luk ( 東涯新錄 ) AKA "The Orientalist"

This newspaper and its predecessor both had the same editor, Lee Kan ( 李根), born in 1825 in Fujian, he was a graduate of the Morrison Education Society School when it was located in Macao, and it seems had been brought to the USA specifically to aid with missionary efforts to the new Chinese community emerging in California during the gold rush. While little is known about this fascinating person I hope to write a full column about him and his life in the future. (The section on Lee Kan, just grew and grew until a decision was made to cut it and make it into a separate column of its own. This frequently happens when writing this column.) 3

Articles and Where to read the paper today

While one can see the articles and the newspaper in their original form at the links shared both above and below, I have one source where someone has taken the time to retype pieces from the original. While this reduces some of the charm, it also makes them much simpler to read.

California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences, Volume 3, Number 3, 18 January 1855

"The Oriental" newspaper was published by Reverend William Speer.

See https://www.frederickbee.com/1855.html

January 25, 1855 The Chinese Companies article in The Oriental

38,687 Chinese immigrants in California. However, this count could have been 1,000 more according to the article.

and

March 1, 1855 Internal Order of the Chinese Companies in The Oriental

Yeung-Wo regulations enumarated.

Courtesy of the San Francisco Theological Seminary

and

Constitution of the Yeung-Wo from William Speer's book published in 1871.

and

Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco Upon Governor Bigler's Message

The two articles in the Oriental are also in these remarks.

and

The Chinese six companies; a short, general historical resumé of its origin, function, and importance in the life of the California Chinese, by William Ho

January 25, 1855 stone for Washington Monument article in The Oriental

Finally as shared above:

If you wish to read the article in full, two English language editions of this paper can be found here, https://delivery.library.ca.gov:8443/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE326066&fbclid=IwY2xjawKW8YlleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETE3bVdLcXJwdW1Sb3VNUkhZAR6a6LX4pa9JeGtmnvS_0UTuLn6Dw3kxk0v57hSS7xO7dSIz4RJqC-Q6wNCd9w_aem_CSmvhykCQZA99j4zeiLy_g , courtesy of the California State Library.

Although the quality is not as good, the entire two years of the paper can be found online here, at Archive.org, both Chinese and English language versions. It’s fascinating reading and browsing: https://archive.org/details/per_tung-ngai-san-luk_tung-ngai-san-luk_january-1855-december-1856_ia40330207-26/page/n93/mode/2up

Footnotes and Refences

According to Unschuld, Paul U. (1985) University of California Press, the history of Western allopathic medicine in China is largely tied in with missionary activity.