The History of the History of the Image of the Ninja, Part Two: Globalization

This one is a day late, due to my attendance at the FDNY Search and Rescue Conference. Please enjoy and leave a comment below.

If you haven’t read it yet, this is the second half of a two parter so please check out last week’s piece, Part One.

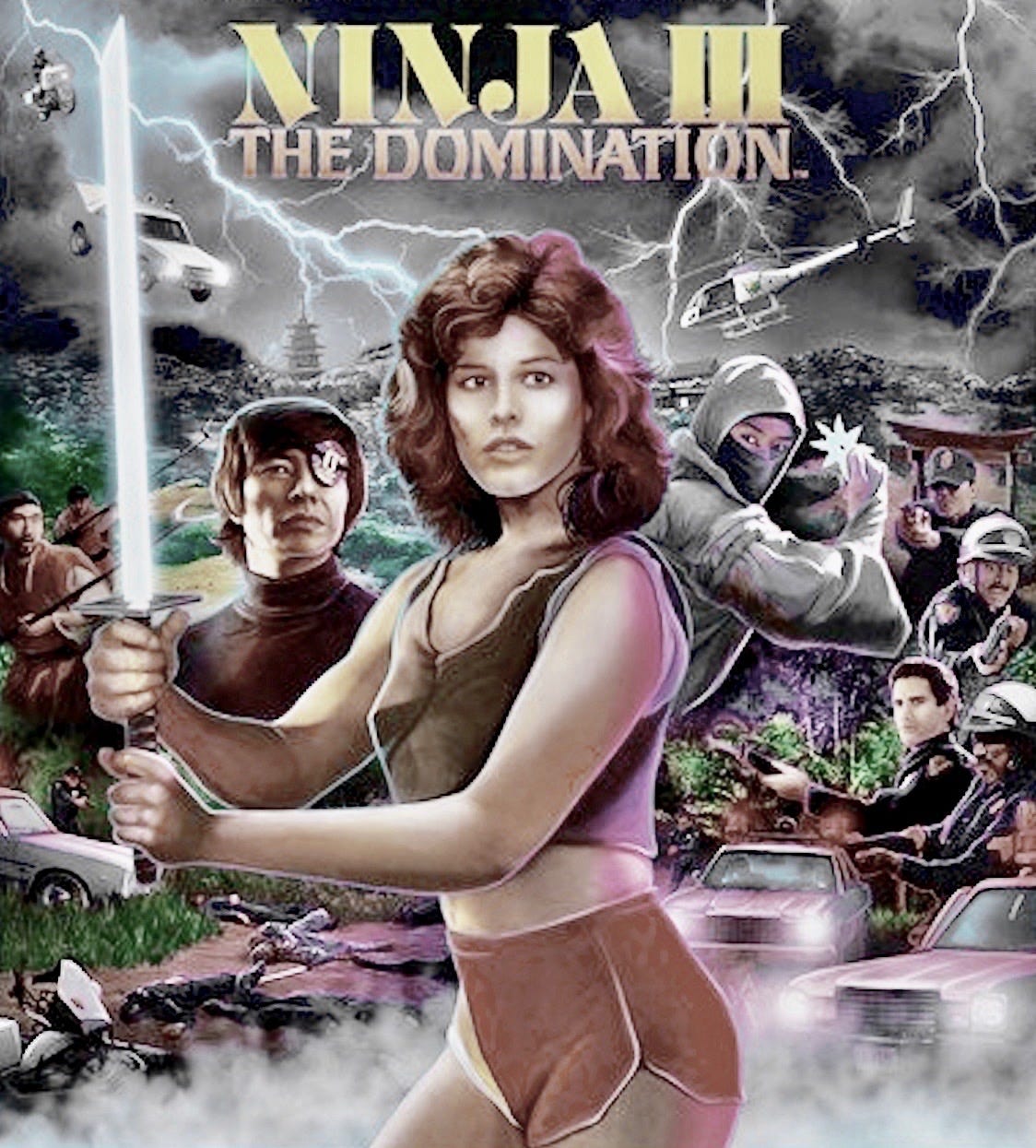

Lucinda Dickey forever!!

Long live “Ninja III: The Domination”!!!

Ninjutsu and the Image of the Ninja Becomes Popularized and Goes Global

Last week, I argued that ninja did not exist during the time when the Samurai wars took place. Instead, I claimed, that image arose during the twentieth century, and that it arose from an attempt to take some claims of magical beings called ninja and find a more rational explanation for the things that they were supposed to have done or been credited with doing. For instance, instead of jumping off a wall and magically floating to the ground unharmed, claims began to be made that these beings were people who had jumped off a wall and floated to the ground unharmed because they were wearing a parachute, despite the awkward fact that parachutes had not been invented yet.

I named three people as being particularly prominent in this process.

They were:

Fujita Seiko 藤田 西湖 (1898-1966).

Okuse Heishichirou 奥瀬平七郎 ( 1911-1997).

Hatsumi Masaaki 初見 良昭 (1931- still living ).

I argued that althoughI am still doing research, I currently theorize that all of the major appearances of the spread of ninja and ninjutsu that entered the west before the 1980s, had some connetion with at least one of these three people.

Ninja and Ninjutsu Enter the West

Going quickly, some key events:

1960s

1964. Ian Fleming’s popular James Bond novel, “You Only Live Twice,” is published and does very well. Much of the story is set in Japan and the plot features ninja. This seems to be when the word “ninja” first appeared in the English language (more on that argument in a future piece.) I do not, at this time, yet know where or how exactly Ian Fleming first learned of ninja. I hope to eventually learn this. I suspect there is probably a connection to Donn Draeger, but I really don’t know at this time.

1967. The James Bond film, “You Only Live Twice,” starring Sean Connery is released and also does very well. The film features a climactic ninja assault led by James Bond and Tiger Tanaka of the Japanese Secret Service on the secret headquarters of Ernst Blofeld, the villain. To most Americans and other Westerners who saw the film, this was probably their first exposure to the concept and image of the ninja.

Donn Draeger, well known martial artist and influential martial arts author, was a consultant with the film. Draeger had contact with Fujita Seiko.

1969. “Asian Fighting Arts” by Donn Draeger and Robert W. Smith was published. Later rereleased under the title, “Comprehensive Asian Fight Arts,” Smith and Draeger were both legitimate and recognized authorities on Asian martial arts. It was a groundbreaking work and a very sensible introduction to the vast subject of different Asian martial arts, and it included 11 pages on ninja and ninjutsu. This section, in hindsight, need to be re-examined including the claim that ninja of the classical age used to hang from giant kites for night time assaults on castles. (p. 128) This book lists “S. Fujita” among those who helped share information. As Fujita had passed away in 1966, I take this as a sign of how hard and long Draeger had worked on his book.

On page 130-131 of my copy of Smith and Draeger's work, a 1985 fifth printing, the book states “The late Fujita Seiko was the last of the living ninja having served in assignments for the Imperial Government during the Taisho and Showa eras. No ninja exist today. Modern authorities such as T. Hatsumi are responsible for most research being done on ninjutsu .”

I hope to do more research on this in the future and establish what if any connection existed between “T. Hatsumi” and “Masaaki Hatsumi” and if it is possible that they are the same person.

1970s

1970. Andrew Adams, “Ninja, The Invisible Assassins” was published. In his introduction, Adams thanks Okuse and Hatsumi for sharing information in his introduction and much of the information and photos came from the ninja museums that Okuse had worked hard to establish and promote.

1971. Donn Draeger’s “Art of Invisibility, Ninjutsu” was published.

A second book containing ninja claims from Donn Draeger, “The Art of Invisibility, Ninjutsu,” was published in 1972. It contains a description of ninja very similar to that in Andrews’ book . While the book has no bibliography or footnotes or accreditations, I think it’s fair to say that it builds on at least the information provided by Fujita but I find it difficult to imagine that Draeger did not at least visit the ninja museums and at least try to meet with Okuse, a man who probably would have been eager to meet with him. I hope to look into this more later.

The book also has a preface by Jack Seward, a long time American ex-pat who lived in Japan and wrote a book entitled “Hara Kiri, Japanese Ritual Suicide,” published in 1968. Like the Turnbull books on Samurai warfare mentioned above, I read it decades ago, thought it quite good at the time, but am absolutely unqualified to judge its quality or accuracy if asked to do so. I will say, speaking as an experienced teacher of English as a Second or Additional Language as well as a life long language learner, another of Seward’s books, “Japanese in Action,” published in 1968, is a truly wonderful book, although for the record it has absolutely nothing to do with ninja or ninjutsu. Delightful, funny, and extremely useful, that book deals with the challenges of trying to learn Japanese as a Caucasian living in Japan with many of these obstacles based in the local culture, the extreme politeness of the local people, the local desire to display and use their own knowledge of English no matter how awful, and the Japanese stereotypes of foreign people and foreign people who learn Japanese, and how these all pose obstacles and challenges to someone who really wishes to learn the local language to a high level. Having a foreword by Jack Seward in a book published in Japan at this time was seemingly a strong endorsement of a book’s quality and contents.

Draeger’s ninja book is still print today, 53 years later, and still popular.

The 1980s -The 1980s Ninja Boom and Beyond

In the 1980s, there was an explosion of popular interest in Ninja and Ninjutsu in the USA.

1980, Stephen Hayes’s book, “Ninja, Spirit of the Shadow Warrior,” was released by Ohara, the same company that published Andrew Adams’ book. It was the first in a series, and taught readers how to perform and practice ninjutsu skills. Hayes had studied in Japan under Masaaki Hatsumi and went on to become a very prolific author of ninja books and undoubtedly America’s best known and most respected instructor of ninjutsu. More on him and his activities in the future,

1981, “Secrets of the Ninja,” authored by Ashida Kim, the pen name of a White American whose actual name is in dispute, was published by Citadel Press. It too claimed to teach the reader ninja skills and how to practice ninjutsu. Ashida Kim has never actually given a full account of where he learned ninjutsu. Nevertheless, he has gone on to be a very prolific author of many books, some, to be frank considered quite silly and bizarre, as well as offered many interviews and even videos on his martial arts and ninjutsu accomplishments.

In the future, I hope to write more on Kim and his works in the future, and to spend time sharing the wonders of my Ashida Kim book collection. (Remember how I said this publication was going to include explicit, smutty sexual content? I own a copy of “The Amorous Adventures of Ashida Kim,” yet somehow have never read this attempt at martial arts themed erotica. – And, yes, this is a real book that he wrote. - -I am still trying to obtain a copy of “X-Rated Dragon Lady,” another notorious Ashida Kim book that apparently even he decided was too bizarre and took out of print. If anyone can help me obtain a copy or send me a PDF or scan of the book, I will be eternally grateful. Please note that Ashida Kim’s “X-Rated Dragon Lady” is not to be confused with his book “Dragon Lady of the Ninja” which I already own. “X-Rated Dragon Lady” and “Dragon Lady of the Ninja” are different books, although both were written by Ashida Kim.

Obviously, Ashida Kim deserves more space and I have begun an introductory piece on him and his works.

In the meantime, to learn more, visit

Um, it’s a memorable experience to explore the works and thoughts of Ashida Kim.

Ultimately, the ninja boom of the 1980s took off with ninja becoming a frequent feature in comic books and b-movies.

Ultimately the craze became so big that in 1984, two young American guys release a satirical comic book making fun of not just ninjas but trends in comics such as the X-men with its endless array of super-powered teenage mutants. It was, of course, called “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” and the rest, as they say, is history.

Turnbull and his Three Books

Which brings us back to Stephen Turnbull, the prolific and very popular author of many books on Japanese military history of the Samurai era, as well as other subjects.

As an author of pre-modern Japanese historical non-fiction books, Turnbull has written three signifant books on ninja history. Interestingly enough, they show a complete change in perspective and conclusion as time goes on.

Ninja, The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult, copyright 1991

The first, “Ninja, The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult,” was published in 1991, by Firebird Books, a popular press that published books on warriors and warfare. It was presented as the first book explaining in English the actual history of ninja and ninjutsu by an author knowledgeable and experienced in the history of their era. It was accepted as such and met with a ready audience who embraced the book. ( A quick check at Amazon reveals that the book has 28 ratings from readers with an average rating of 4.7 on a 5 star scale, By contrast, Goodreads shows 63 ratings with an average of only 3.68 with some readers questioning how much of this is actually true.)

At the time, I, like most readers and with the same approach as I took to the other Stephen Turnbull books, believed it to be true. After all, if Japan has ritul suicide, and people who devote their lives to origami and folding paper birds, and its navy in world war two used kamikaze planes and even created the Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka self-propelled suicide rocket bomb, why would it not have people trained from birth to be assassins back in the samurai days?

And that’s the way it was accepted. Turnbull credits both Okuse and Hatsumi with being great help to him in writing the book and spent a great deal of time visiting the museum’s that Okuse helped create and promote. He even includes a photo of himself and Hatsumi together in the introduction.

Ninja, AD 1460-1650, copyright 2003

In 2003, Turnbull wrote a second book on the subject, this one for Osprey Publishing. Osprey Publishing is basically a press that produces much loved yet thin books aimed at military hobbyists, re-enactors, and wargamers. Their books are well known for their lovely, full color illustrations showing warriors and soldiers of the past as interpreted by the author and illustrator. Turnbull has done a lot of work for Osprey and written many books for them.

This book covers similar ground to the above book, but in a slightly different way and for a different audience. This one has 55 ratings at Amazon with an average rating of 4.4. At Goodreads, the book has 106 ratings with an average rating of 3.65.

For sources, he recommends people see his earlier book on the subject, described above, and thanks the ninja museums for their assistance.

So now we have a pair of books on ninja written by prolific and well-received author known for writing popular books on military history many of which focused specifically on the era in which ninja were said to exist. It seems only natural that people would take these books and their contents seriously.

As if to pound in the lesson that ninja as described in the popular image were real, Turnbull went and wrote two more books on the ninja. These were a 2008 children’s book entitled “Real Ninja” and a tongue-in-cheek book entitled “Ninja: The (Unofficial) Training Manual” was released in 2019 but apparently written earlier. I have, at this time, read neither of these, but I do have second copies now mail ordered.1

Meanwhile, academics, for reasons described in a previous piece here at STAFI, tended to just stay out of the issue of ninja truth or fiction, at least publicly. In private the attitude was sort of “why do people believe these stupid things?” but for many reasons having to do with the structure of academia and the way academics are rewarded and activities that their peers respect and don’t respect, these complaints tended to say pretty much private. 2

Ninja, Unmasking the Myth, copyright 2017

So far, ho hum, more of the same, but in 2017, Stephen Turnbull released both an academic paper and a book where he had come to a particularly interesting and dramatic conclusion. Essentially, Turnbull argued that pretty much everything he had written in his previous books on ninja was wrong. He had, he explained, misinterpreted and misjudged his sources.

This is a pretty amazing thing for anyone to do, much less an author of history, and I am personally amazed, stunned, and impressed with Turnbull for doing so. In his book, “Ninja, Unmasking the Myth” and his earlier, 2014 paper, “The Ninja: An Invented Tradition?,” Turnbull argued that the modern conception of the late medieval Japanese Ninja was, in fact, an invented tradition. By this, he meant that the concept had arisen much later, with some Japanese accepting it as fact and history and embracing the factually incorrect idea that their ancestors had been ninja who studied the art of ninjutsu and had been capable of superhuman feats which they had performed back in what I called “the era of the last great Samurai Wars.”

From there, the next step had been the spread of the idea to the USA and the West where others had taken it up and, in turn, declared themselves to be ninja who studied and practiced ninjutsu as well.

This is an exciting and interesting idea and one I will explore more in STAFI. Please stay tuned, please subscribe, and please share these writings in forums where people might enjoy them and with your friends. I hope to build up my readership.

Previous S.T.A.F.I. Articles on Ninja Historiography

The Ninja Articles Begin -Enter the Ninja!

The History of the History of the Image of the Ninja, Part One, Enter the Concept and the Image of the Ninja

POSTNOTE:

Someone is going to ask how much of what I am writing here is original research and how much is simply a rehashing and summarzing of Turnbull’s arguments in “Ninja, Unmasking the Myth”? Honestly, at this point, I can’t say. It’s been years since I read “Unmasking the Myth,” but I hope to reread it soon. Some of what I have written here is completely unmentioned in this book, i.e. Ashida Kim’s role in all this, while in other cases, I suspect that what I am discovering here on my own are things that he mentioned or described, that I then forgot or perhaps didn’t absorb at all, and am now finding on my own even if he found them first. In any case, I think it’s fair to say that while I am writing “my own thing” and heading off in my own direction in an original manner separate from Turnbull, there’s clearly an overlap, and it’s unlikely I would be doing this project if he had not written his paper on invented traditions which I stumbled across and then found his book.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

English Sources.

Adams, Andrew. Ninja, the Invisible Assassins. Burbank, CA: Ohara Publications. 1970.

Draeger, Donn & Smith, Robert W. Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. Tokyo, New York, & San Francisco: Kodansha International, Ltd. Copyright 1969, Fifth Printing, 1985.

Draeger, Donn. The Art of Invisibility: Ninjutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Simpson-Doyle & Company. 1971.

Hayes, Stephen K. Ninja, Spirit of the Shadow Warrior. Burbank CA: Ohara Publications. 1980.

Kim, Ashida. Secrets of the Ninja. Secaucus NJ: Citadel Press. 1981.

Serebriokova, Polina & Orbach, Danny. “Irregular Warfare in Late Medieval Japan: Towards a Historical Understanding of the ‘Ninja.’” The Journal of Military History. 84 (October 2020) PP. 997-1020.

Seward, Jack. Japanese in Action. New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill Books. 1968, 1976. Reprinted by Lucky Book Company, Taiwan, 1984.

Turnbull, Stephen. Ninja, the True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult. Dorset UK: Firebird Books. 1991.

Turnbull, Stephen. Ninja, AD 1450-1650. Oxford UK: Osprey Publishing. 2003.

Turnbull, Stephen. “The Ninja: An Invented Tradition?” Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective. Vol. 9, No. 1. PP. 9-26.

Turnbull, Stephen. Ninja, Unmasking the Myth. S.Yorkshire, UK: Frontline Books. 2017.

JAPANESE LANGUAGE RESOURCES

Wikipedia, 奥瀬平七郎 “Okuse Heishichiro.” https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/奥瀬平七郎b accessed April 19, 2024 (autotranslated with Google Translate).

These books have now arrived. If you wish to encourage me to read them, share these writings and get people to subscribe, ideally with a paid subscription.

One exception is the following journal article:

Serebriokova, Polina & Orbach, Danny. “Irregular Warfare in Late Medieval Japan: Towards a Historical Understanding of the ‘Ninja.’” The Journal of Military History. 84 (October 2020) PP. 997-1020.

Honestly, I was not a big fan of it.