The Hakka Chinese - Hong Kong connection of the 1840s, and the California Gold Rush, Part One

More on the California Gold Rush, Chinese mass violence in 1850s California, the Saga Continues

Greetings! Thanks for coming back or welcome aboard for new people.

As people may recall, one of my other activities is doing EMS and ambulance work, and I have been busy taking an intensive class called the Advanced EMT. Basically, the class takes EMTs, reviews and expands everything they know, and then gives them further training on a wide variety of subjects, most notably starting I.V.s on people and administering a few additional drugs, and ensuring they have a better understanding of pathophysiology and related subjects. The course comes to an end shortly.

Which means as we head into 2025, I hope to have more time for this column. While I am proud of what I have done and what I am doing here, creating weekly content on Chinese or Asian history and related subjects aimed at lay people since March 2024 with well over 50 columns published, and many more on many subjects that I look forward to writing (I have no shortage of ideas for future columns, by the way), there will be changes in content and approach. The goal will be to increase readership and increase income from this endeavor. While I expect to have regular offerings of free content, there will be some content available only to paid subscribers. This is a reader supported column which means there is no advertising, and any money that comes from writing it comes from the readers, and I would like to be better compensated for this writing. So there will be a mix of free content and content for paid subscribers only. If this worries you, and you fear being cut off, I suggest liking and commenting on any and all columns from now on, and I will probably comp you a free subscription to paid content. If that doesn’t work for you, and you still think you are special, and you might very well be special, please reach out and communicate with me directly.

My hope is to have something short and interesting and free of charge each week, combined with paid content of various types. Details will emerge as we head forth into the future, and there will probaby be a period of trying things out and seeing what works.

I also plan to do a thorough review on how people market and publicize these things, as well as assess and redo the materials new subscribers and non-subscribers see when they take a look at the column. So expect to see more social media posts in a variety of forums on Mostly Asian History and this column.

If you like what you see here, please support it by sharing the posts and letting people know it exists. And please don’t forget to like, leave a comment, or consider upgrading to a paid subscription. As always, I have included not just an original column, but also links to a couple of videos that will enhance or add to your understanding of Asian history and the subject discussed here.

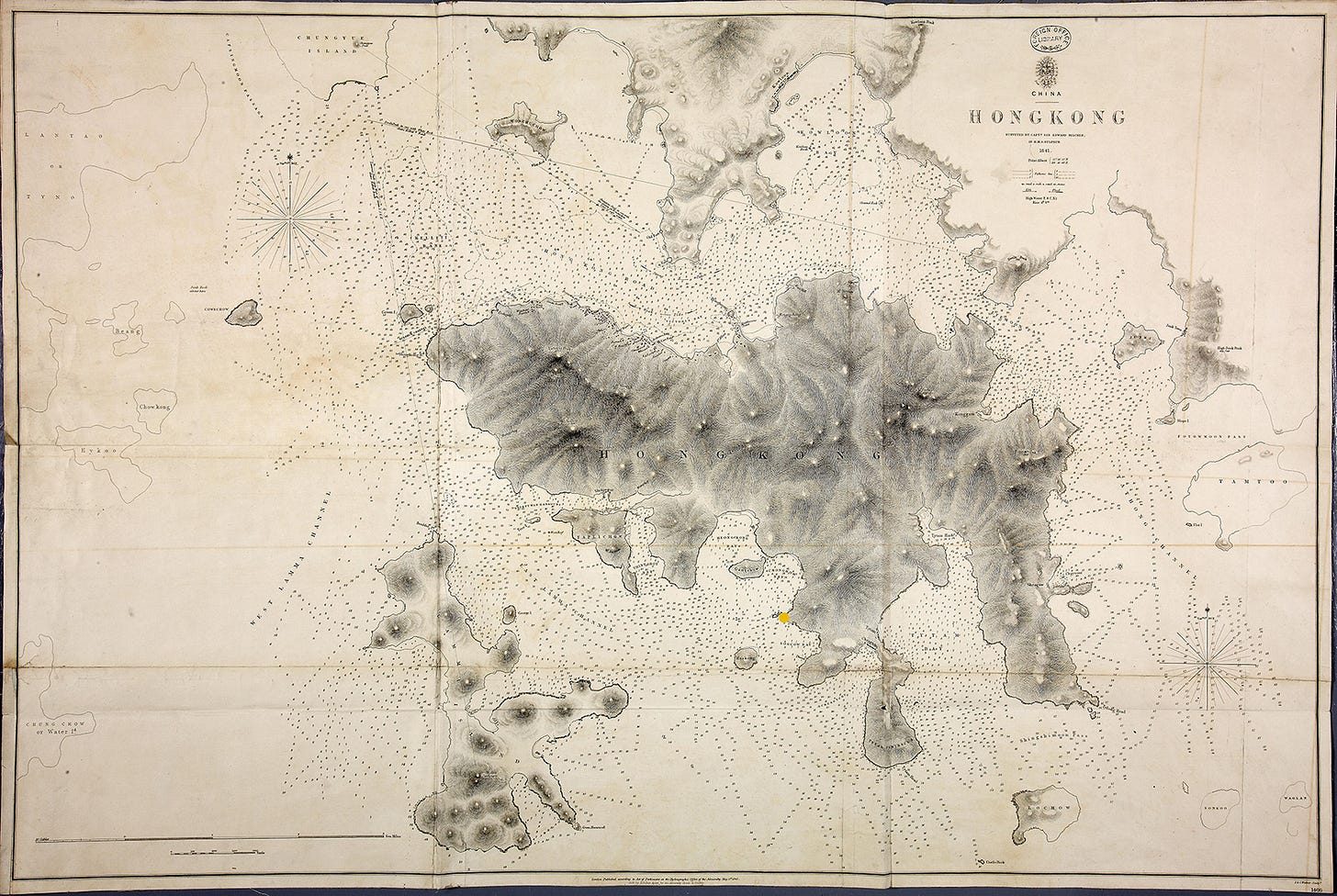

A British map of Hong Kong island in 1841, the year before it was acquired from China. Note that this focuses on the island. The nearby peninsula now known as “the New Territories” was not originally part of the territory. The expansion of Hong Kong territory is covered in the video, i share below, with the large peninusla added in 1898 with a 99 year lease that expired in 1997. When the lease expired, the entire city both the island and the peninsula were reverted to Chinese control after negotiations.

Quick rehash for anyone who is new. For the last few months, 80% of what I have been writing about has involved Chinese-American history and lately Chinese during the California Gold Rush that started in 1848 or 1849 depending on the definitions one uses. This was not planned, but I stumbled across something very interesting and just kept digging in order to understand it better.

In 1854 in Weaversville, California, and again in 1856 in the town of Chinese Camp, California, two large groups of Chinese announced they were going to fight each other, made a big display of purchasing weapons while publicly threatening each other, then, and this happened in both places, they faced off and fought each other while the rest of the local, mostly White population of these isolated places watched all the while wondering what all the fighting was about as it made no sense to them.

Well, the issue of who these people were and why they were fighting, is actually a very good question. Therefore, I am actively digging into it and exploring that question —"who were these people and why were they fighting?”- in a way I have never seen done anywhere else. While doing so, I find myself doing a great deal of what is called “transnational history,” which means taking events in one place and putting them in a global context. And thus today, in order to better understanding these conflicts in California, we find ourself looking at events in Hong Kong and Guangdong province, often referred to in the West as “Canton.”

THE STORY SO FAR . . .

What we’ve learned so far is that although the local, mostly White observers described these events as “tong wars,” a “tong” being one name for a sworn brotherhood where men voluntarily chose to swear oaths promising loyalty to the group and its members. These groups existed not just in China but in overseas Chinese communities throughout the world, and sometimes violence did break out between them.

But we do know the names of the groups. The observers and some of the participants who wrote about these events named the groups involved. Some members of the group also wrote about the event The groups were called the “Sam Yep” and the “Yong Wo,” with much variation in the spelling of these names. With this information, we can identify the organizations involved, and learn more about them and their members. And we did so.

They were not “tongs” at all but instead “regional associations” or as they were often known “Chinese companies” or members of what was later known as “the Chinese Six Companies,” even though there were not yet six of them at this time. These organizations became the most important members of what is today known as “the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association” or the C.C.B.A. The C.C.B.A. still exists and usually has chapters in the older Chinatowns in North America. I used to take Hung Gar Kung Fu lessons at the Boston branch, although for the record, I do not claim much skill in this art although it was a lot of fun.

These “companies” were organizations based on one’s hometown and region of origin in China, and membership was involuntary. They were run and dominated by the wealthy Chinese merchants in San Francisco Chinatown. From the moment newly arrived Chinese stepped off the boat in San Francisco harbor, to the moment they got back on the ship to return home to China, these organizations had a great deal of control and influence over the lives of the Chinese workers and miners in California.

To quote from an earlier column, we had two groups:

“The “three counties” organization still exists today and has headquarters in many of the older Chinatowns and even has its own Wikipedia page.”

And:

As for their opponents in these conflicts:

These were the Yeong Wo (Chinese: 陽 和) company. They came from Heung-shan, Tung-kun, and Tsang-shing districts, and the organization was founded in 1852. It also included the Hip Kat company, formed by Hakka immigrants from Bow On, Chak Tai, Tung Gwoon, and Chu Mui districts, in 1852.[13]

This organization, which also exists today, was composed of Hakka Chinese, a sub-group of Chinese that did not normally speak Cantonese but instead spoke the Hakka dialect.

For more details, see California Gold Rush "Tong Wars," and the non-"tong"" organizations that really fought them, Part Four in a series on the California Gold Rush "Tong Wars" and California Gold Rush "Tong Wars," and the non-"tong"" organizations that really fought them, Part Four in a series on the California Gold Rush "Tong Wars."

Each of these groups were from a different region of the Pearl River Delta in southern China. Not only that, but they represented two different Chinese sub-groups, the Hakka and the Cantonese. As discussed in previous columns, these can easily be seen as different ethnic groups although some, notably the Chinese government, would argue otherwise. Even though they were and are both Chinese, and both classified as “Han Chinese” by the current government of China, they spoke different dialects, ate different cuisines, had different styles of architecture, and had slightly different styles of clothes and religious practices.

This was also discussed in previous columns. See Who are the Hakka Chinese, and What are Chinese sub-groups anyway, Part 5 in a series on Chinese conflicts during the California Gold Rush? and Hakka Cultural Characteristics, Part 6 of Chinese conflicts of the California Gold Rush

However, there was one particular fact mentioned in the historical reports that struck me as particularly interesting and surprising that we have not covered. In the historical reports, the “Sam Yep” company members are described as being from Canton also known as Guanzhou. This fact, however, is not particularly surprising as it makes sense as Cantonese people are generally from Canton, either directly or indirectly.

However, and this was particularly surprising to me, the historical reports said that the “Yong Wo,” the Hakka organization, was composed of people from Hong Kong.

As one of the group’s, the Yong Wo, are said to be “Hong Kong Men” and not “Canton Men.”

Well, after a couple weeks spent on other subjects this week we finally come back to the connection between the Hakka and Hong Kong.

WHY WERE THE HAKKA DESCRIBED AS THE “HONG KONG CHINESE”?

This connection surprised me. I thought I was relatively familiar with the Hakka sub-group. I have known several Hakka people in several places. I thought I was relatively familiar with Hong Kong. I’ve been there several times, enjoyed countless Hong Kong films, and read a great deal about its unique history.

But I had never put the two together or seen anyone else do so.

So what was the connection between Hong Kong and the Hakka ethnic group in the 1840s?

I had never heard of such a connection, but there it was, clearly described and documented by people of the time.

So . . . I researched it. The connection came about largely through a multi-step series of events or conditions. Like a lot of history, they flowed into each other, causing each other.

Basically, the events and conditions that led to the Hakka being associated with Hong Kong in the 1840s and being described as “the Hong Kong Chinese” in documents from the California Gold Rush are as follows:

1. The Hakka come down from the north seeking homes and areas to settle. This has been previously discussed.

2. Widespread piracy and banditry was common in China.

3. Some of these pirates were so important that they were a major factor in political events.

4. In the 17th Century, the Manchus or Qing Dynasty were trying to consolidate their rule, and Ming Dynasty loyalists and their pirate allies were a problem in this consolidation. They responded to the wide spread presence of pirates with something called “the Great Clearance” ( 遷界令 or 遷海令 ) forbidding people to live on the coasts of China. This was to isolate the population from the pirates and smugglers, and thereby cut off the support and supplies to the pirates. The Great Clearance was not a single event, but actually a series of edicts that were occasionally lifted or modified and then put back in place. The first one was ordered in 1661 and the last one rescinded in 1683.

5. When this was repealed, later in the 17th century, a lot of coastal areas were not just uninhabited but suddenly legally opened to coastal settlement. Many of the people who had lived there either had no desire or lacked the ability to resettle in these areas.

6. Many Hakka, a people often desperate and seeking homes, moved to these coastal areas including settling on Hong Kong island. At the time Hong Kong island was an unimportant place and not a major city or seaport.

7. At the end of the Opium War in 1842, Britain was seeking its own seaport on the coast of China, something that would compete with Macao, a Portuguese controlled seaport on the coast of China, and seized Hong Kong island and began building it up into the major city and commercial trade center that it is today. At the time, the island was largely inhabited by Hakka people, although many other kinds of Chinese, including very large numbers of Cantonese people, came in subsequent decades. This explains why in the 1840s in California, the Hakka were associated with Hong Kong, but today they are not. This was just 6 or 7 years before the California Gold Rush happened, and the finding of gold in California and the founding of Hong Kong as a British trading port both affected each other in several very interesting ways. Although most Americans do not realize it, the California Gold Rush was an event of global importance, which makes sense if we recognize that people were leaving their homes and moving to California from places like Hong Kong, Canton (Guangdong), Chile, and Australia, and other places throughout the Pacific while others throughout the region, including Hong Kong were doing everything they could to ship and sell supplies to the miners seeking their fortunes in California.

As always expect more on this in upcoming columns.

BONUS VIDEOS!!

Again, as always, I offer these bonus videos to enhance your understanding.

First a video on the early history of Hong Kong. The great clearance is mentioned at about the 8:00 point.

Second, having written a great deal about the Hakka Chinese, a group that was present in California during the Gold Rush and formed one side of the conflicts in 1854 and 1856, I thought it worthwhile share this video about Hakka language diversity. It also shoud give insight into why the Chinese government mandated the use of Mandarin as a spoken language for all Chinese and discourages the use of other Chinese dialects in several ways. As you can see, not only is there a distinctly different Hakka dialect of Chinese, but there are widely varying styles of Hakka and Hakka speakers from different communities often have trouble communicating with each other. It’s probably not something any of you would wish to watch from beginning to end, unless, of course, you have a strong interest in Chinese or Hakka linguistics, but watching a minute or two should make it clear that there are many varieties of even one Chinese dialect.

Also of interest is that the presenter at one point describes her style of Hakka as Surinamese Hakka, the Hakka of the Hakka community of Suriname (sometimes spelled Surinam). I confess I had to look up where that was, and it is the former Dutch colony on the North East Coast of South America formerly known as “Dutch Guyana.” Yes, if you did not absorb it previously or did not believe me, the Hakka Chinese get around and have settled in some very interesting places besides Hong Kong and California.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aside from the books, I have used previously for these columns, here are a few of the sources I used this week. Some were from portions that will be used in future weeks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Clearance

https://gwulo.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qi_Jiguang#

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wokou

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiajing_wokou_raids

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koxinga

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://hkjo.lib.hku.hk/archive/files/1456f650fd5455b7f60085907e5fc462.pdf

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zheng-Chenggong

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/hong-kong-and-the-opium-wars/

The CCBA is still important in Portland's Chinese community. Its public activities include business networking, festival observance, Mandarin classes, and similar. It's just a couple blocks from the Hop Sing Tong's building inChinatown.