Readings from an early Chinese Gazetteer -Natural Disasters in the Hong Kong and Shenzhen region prior to the British

An Introduction and excerpts from the Xinan County Gazeteer of 1819 with a focus on Natural Disasters

Greetings,

First, I have now finished my Advanced EMT course, although I am awaiting scheduling of my ceritification test. Therefore, expect some changes to this newsletter over the next couple months. The intent is to increase readership and income from this project

Research has begun on creating a better social media presence. Expect details soon.

One goal is to have pieces written several weeks ahead, and expect some content that will be for people with paid subscriptions only. If you are here now, and think you deserve a comp subscription for paid content, either like or comment regularly or else reach out to me and we can talk about it.

Last time I mentioned that historically the Chinese coasts have had a terrible problem with pirates and piracy just as the mountains and forests have historicaly often had a terrible problem with bandits. I also mentioned that a Chinese sub-group called the Hakka had become associated with Hong Kong, although they lived in many other places as well, and this is why during the California Gold Rush, the Hakka were often thought of as “the Hong Kong Chinese” by the other, mostly White miners and other recently arrived setters in California at that time.

For several reasons, I decided to take a brief break from Chinese-American Gold Rush history, and instead focus on some of the things I am learning or uncovering about life in China, often from the same sources. So today we are focusing on life in southern China before the British gained political control of Hong Kong island in 1842.

Enjoy! As always, please feel free to share, like, or comment. Thanks for stopping by and taking time from your busy schedules to look this over.

An 1866 map of the region covered in the 1819 Gazeteer. This map was created largely based on the work of an Italian missionary, Simeone Volonteri, 1831-1904, based in Hong Kong. It’s often considered the first good map of the region ever made. At this time, Europeans and Westerners made more accurate maps than the Chinese. 1

Over the last few weeks, we have learned a bit about life in the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong (Canton) during the early 19th Century as that was the region where almost all Chinese who went to California during the Gold Rush came from.

We learned that life was desperate and harsh there, that there are several Chinese sub-groups including the Hakka and the Cantonese, 2 and that piracy was been a widespread problem in the coastal areas of China throughout most of China’s pre-modern history. We also learned that when the British gained control of Hong Kong island in 1842, a lot of the Chinese living there were Hakka.

A lot of the details of that came from a book was published in 1819 called the 3Xin'an Xianzhi ( 新安縣志). This translates as either the Gazetteers of Xin'an County, or since “Xinan” translates as “New Peace” the title could also be translated as “the Gazetteer of New Peace County.” 4

It was the sixth Chinese “gazeteer” about the region, a “gazeteer” being basically a compendium of facts and data in book from about a place so that people who had a need or desire to know more about the place could find relevant information about it in book form. The first such book about the region was published in 1587. The 1819 edition was the last published before Hong Kong island was turned over to the British in 1841 and the region changed forever.

In 1961, a man from Hong Kong named Peter Y.L. Ng wrote his master’s thesis about this edition of the gazetteer and in 1983, the master’s thesis was updated and revised and used as the core for a 1983 book published by Hong Kong University Press. The book was entitled “New Peace County, a Chinese Gazetteer of the Hong Kong Region.” 5 It makes interesting although at times disorganized and confusing reading. I say this not as an attack, but simply because the standards and ways of doing things were different to the people of this time, and at times the things they thought were important and should be recorded are not the things we wish they had written.

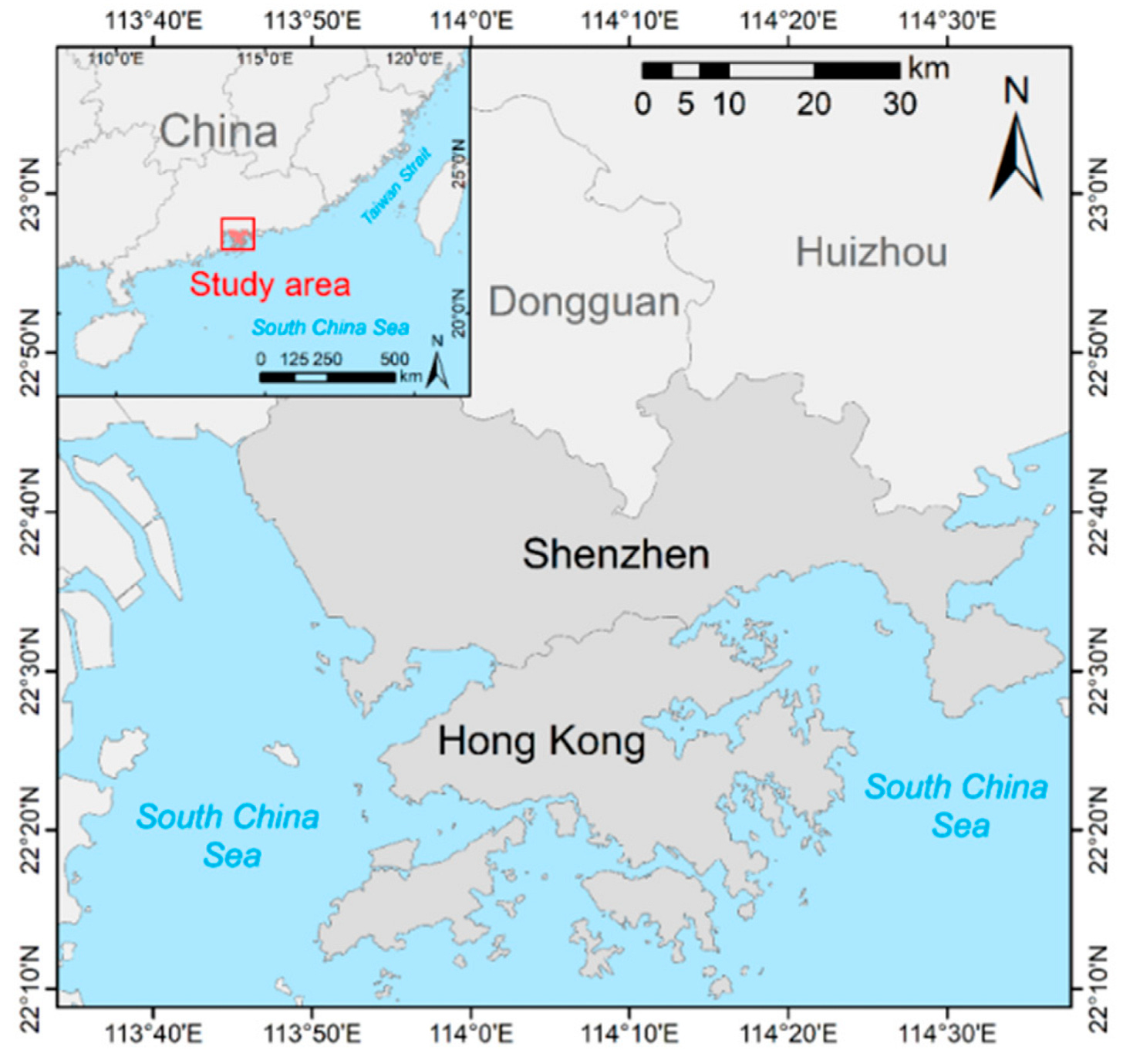

While Xinan County no longer exists, we know where it was. It covered roughly the territory of modern Shenzhen, the special economic zone in Southern Guangong bordering Hong Kong and the entirety of modern Hong Kong as well. See the map below for a modern map of the region.

As stated, we will be looking at a translation of a document from 1819, although one with some commentary. And again, people of the past had a different perspective than people of the present. And this is not just true of China.

Old Documents and Sources, both East and West, often seem a bit alien to readers today

As would be expected, if one reads the writings of people of centuries ago, be they European or North American or Chinese, the perspectives often seem a bit strange to the people of modern times. To give a Western example, years ago, I read a work called “A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson” originally published in 1682. It is the true, horrible, first-hand story of a Massachusetts woman who was taken as prison by hostile Native American Indians in the winter of 1675 during King Phillip’s War, an ugly conflict between hostile Native Americans and the primarily White settlers of Massachusetts and their Native American Indian allies. While it was a very popular book that went through 15 printings between 1682 and 1800, with four printings in the first year alone, to a reader of today it’s an unusual read. She tells little of her captors, usually just referring to them as “the Indians.” As for their lifestyle, culture, and point of view, there’s little information save for the terrible atrocities and slaughter they commit on her, her neighbors, and members of her family. But in her defense, she shares little of her own culture either and almost nothing on the greater conflict around her. There’s no real sense of the politics or geo-political context for the war that she’d been a part of. Instead, her focus seems to be on sharing with others the way she used her religious faith to sustain her through the ordeal and the particular Bible verses she recalled or read (when she had access to a Bible, at one point after time spent in captivity “the Indians” gave her a Bible.) To a modern reader, the work seems at times, a perplexing historical artifact, not something that helps to answer the questions that a modern person has about the experience, the conflict it stemmed from, and the people, both White and Native, who were involved in it. 6

Same for “Pilgrim’s Progress,” John Bunyan’s 17th Century allegorical novel about man’s quest for meaning. As this was one of three books that my Grandmother in turn of the century Maine had in her house as a child, I did once try to read it. I did not get too far, and finally gave up, although I did jump at the chance to see the 1978 movie (starring Liam Neeson, no less). Again, tough reading, turgid, slow, confusing, for a modern reader, and often seen as a historical artifact rather than a modern inspirational text. 7

And these are both books that were important to my ancestors from my own culture.

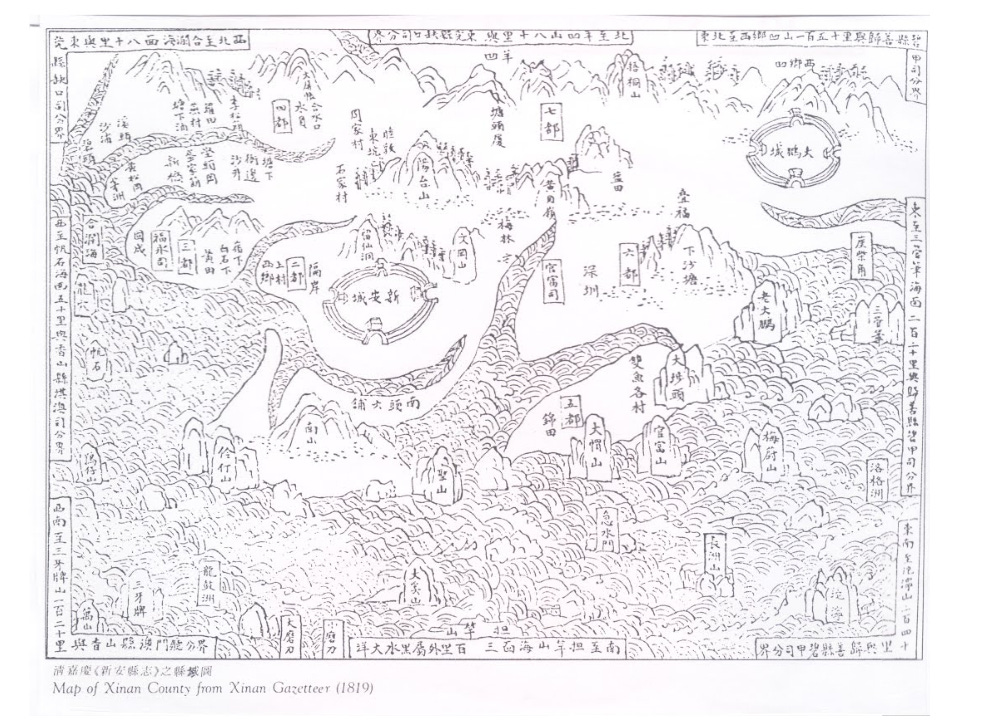

Therefore, it is only to be expected that a work from China pubishled in 1819 would at times be confusing to a modern Western reader. In fact the 1819 map of the region that was published as part of the original book and is show below is itself quite confusing particularly when compared with the above maps. No one had bothered to include Hong Kong Island, for instance, as no one considered the place terribly important or interesting. It does, however, show the same regions as the above maps even if it does not appear to. The land, like on the others, is to the north and the water is shown on the bottom of the map and marked with many jagged lines.

The gazetteer contains a lot of information on many subjects, but today we are just going to give a brief overview of the Gazetteer itself and then look at the section on natural disasters in the region.

THE TEXT, its style and content

First, as Peter Y.L. Ng’s analysis and discussion of the Gazetteer explains, the text itself is not always accurate in its descriptions of the geography or history it describes. Instead it seems to have described things as the officials of the time understood them to be. The original text of the region includes a Chinese map of the region from 1688 and another from 1819, but they are confusing and leaves out key details, including, as stated, but not limited to remembering to include Hong Kong island itself. Who could have had a clue that it would later become the site of the one of the world’s great cities and a gateway between the West and China? In fact, to a Chinese official of the Ming and Qing dynasties or virtually all of pre-Opium War China, it was very unlikely that they would imagine that anything outside of China would be important at all, much less require a gateway city.

Nevertheless, the gazetteer definitely does give insights into not just the culture of the time, but also local conditions and events that were considered important by the local scholar-officials who kept records.

For instance, it has sections on History, Geography, the Economy, and Government of the region covered.

We have reprintings, or in our case translations, of several government edicts from the 16th to early 19th Century designed to make things better in the region.

Some of these are interesting, for instance there’s one from 1728 AD discussing the importance of both officials and the residents of being able to speak in a way that they both can understand and advising officials and locals to work on their accents and stop using local dialects when speaking to each other about official matters. (page 74-75) For better or worse, it wasn’t until the 20th Century that China was able to establish a national dialect that was expected to be learned and spoken by all people.

Another from 1729 AD urges an end to gambling in the region. Alas, that one did not work out apparently. ( page 76).

There are a pair from 1738 and 1743 AD that discuss loans of grain from the government granaries to the people who were short of food until harvest. ( pages 78-79)

Schools, temples, walled and moated cities are all given a brief description, as are the results of local censuses.

There is a description of the annual banquet held for high officials, other local worthies, and their guests, with careful instructions on where each type of person shall sit during the banquet so that all may know how important they are. (page 93-94)

Military matters and postal stations are discussed. ( page 99-100, remember how I said that studying Chinese history is an endless series of rabbit holes? Hmm, I find myself wondering what the Qing dynasty post office was like now that I know they had postal stations. Oh my.)

We have a section called “officials and their good works” ( pages 113-116) and “notable people.” (pages 117-120)

There is even a bit called “Wind lore” that discusses local typhoon patterns. ( page 82)

And there is a lot of stuff here on coastal defence and the issue of pirates and bandits. I do hope to cover that in the future, but for the moment, this week, I have decided to focus on the section on natural disasters instead.

Clearly, it goes without saying, that life was much tougher back then and life more uncertain. Often simple survival was the best one could hope for.

Natural Disasters

For instance, there is a list of “Natural Disasters” that took place between 1526 AD in the Ming Dynasty and 1818 AD during the Qing Dynasty. A quick count shows 66 listed disasters which comes out to about one every four years. The list is on pages 102 to 106 of Peter Y.L. Ng’s book. While some of these are quite serious, others are more befuddling and confusing. To give a few examples of the former, in 1546 May/ June it says “a high tide caused a great flood” and in 1565 “a severe drought brought the price of rice up one a dou.” In 1565, there was an earthquake but in 1578, the list of “natural disasters” says “a comet was seen.”

More perplexing, skipping over many examples, we come to 1630 April/May. The English text says “A sinister omen shaped like a black dog bewitched women. After the County Magistrate Chen Gu had offered prayers to the City God the phenomenon vanished.” In the footnotes, the author suggests that the “sinister omen” may have been an unusual looking cloud. There’s also a mention that in 1647, “there appeared on Qianlong Mountain white vapour shaped like a sheep which changed into a mosquito and moved towards the west. Also the crows cawed non-stop for ten days and nights. Bandits created havoc this year.”

There are even a couple reports of dragon sightings of all things.

For instance, according to Ng’s book (p. 103), in 1652, “nine dragons flew up from Dragon Cave, passed over Chenshang and Chenxia villages and were seen for several li before they disappeared.” 8

And again, on July 28 1669, the book (again p. 103) says “Three dragons, two white and one black rose up from the sea in the west and flew to the south of the city where they caused much damage to housing.”

For what it’s worth, I have reached out and have some leads on how to interpret these passages, but i’m not there yet. Remember how I said “Studying Chinese history is an endless series of going down rabbit holes? It looks like I have found another, but all I will say for now is it’s a mistake to take this at face value. A scholar on the Sinologists group on Facebook told me that such references refer to waterspouts, a phenomenon where a tornado occurs over water. (See: https://www.weather.gov/mfl/waterspouts ) but I suspect there is more to it. It’s been recommended that I read portions of a book called “The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties,” by Timothy Brook that covers this very subject. Of course, I hope to do so, but, alas, I already have about four books waiting to be read on various aspects of Chinese American history in the 19th Century so it’s going to be a while.

There’s always more to these things, and that’s what makes Chinese history fascinating.

Other descriptions of natural disasters are more straightforward, and we have descriptions of drought that damaged or destroyed the crops, bringing either starvation or increased grain prices. These came in the years 1596, 1636,

Aside from that the price of rice rose significantly in the years 1624, 1631,

In 1648, a terrible famine came. The price of rice soared, half the population died, people at corpses for sustenance, and men and women were reportedly sold in to slavery (probably by their family members) in exchange for a “dou” ( 斗 ) of rice which is a unit of about 10.35 liters or a little less than 3 gallons as we are measuring the rice by volume. (page 103) 9 All of this chaos and desperation led to a rise in banditry and robbery. On top of that, there was an outbreak of plague, and in one unnamed village everyone died.

Kind of glad to make me an American who lives in a society where my biggest health risks stem from over consumption of food and alcohol, two things that starving Chinese peasants would have loved to take off my hands probably benefiting us both.

Famine came again in 1653,

Believe it or not, attacks from tigers and wolves were a problem for the population with notably appearances of these man-eating animals in the years 1680 and 1772.

Locusts came in the year 1786 and 1812 eating the crops and endangering the food supply.

Not to mention multiple reports of hailstorms, earthquakes, floods, and typhoons that came blowing things down and damaging property and housing.

As stated, life was much more uncertain back then than it is for us today. And I think we should all remember that and appreciate what we have. Being alive often meant suffering. And this is one of the basic tenets of Buddhism where one attempts to detach oneself from the world around oneself with the end goal being to reduce desire. If successful, the promise is that one will escape from an endless cycle of being alive and cease to exist entirely becoming one with the universe.

Do I believe it? That shouldn’t matter to you. But it something to think about, especially in the context of all this suffering coming at the hands of nature itself. Soon we will discuss what the Gazetteer has to say about threats in the region from fellow humans be they coming from land or sea.

Peace. See you next week. And isn’t it wonderful that we live in an age where I can say that with 99% plus certainty that I will be here next week.

Footnotes and Bibliography

For more details on the map see the following on-line sources:

It’s probably about time to introduce the term “Punti” here. In a lot of 19th Century English writings about the region, the Cantonese are often referred to as “Punti” particularly when contrasted with the Hakka. Therefore Peter Y.L. Ng’s book says, for instance, “Despite the Gazetteer’s careful separation of Punti from Hakka villages and its note of the special examination pass quotes for Hakka men no attempt to made in either the ‘customs’ section of Chapter Two or elsewhere to define what the differences between Hakka and Punti were.” (page 33)

If you are wondering the surname “Ng” is the Cantonese or Hakka pronunciation of the Mandarin surname “Wu.” Both are written with the character 吳

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng_(name) or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_(surname)

If you are wondering how it is prounced it is pronounced like the English words “long” or “sing” with the first half cut off or said silently. Seriously. If you are an English speaker who needs to learn to say it try pronouncing these words but only silently voice the first half of the word before beginnging to say it out loud in the middle of the one syllable word. Seriously. That’s an ESL teacher tip.

Some dastardly wag out there may claim that I did not go to this book, and instead I went to Wikipedia. As stated, although I am finding Wikipedia embarassingly useful, what I did was I went to Wikipedia, carefully checked the sources the Wikipedia contributors cited, and then, seeing this book among them many times, I went out and bought my own copy. So wikipedia led me to this book, and I am reading this book, and I am sharing the contents with you here today.

Ng, Peter Y.L. “New Peace County, a Chinese Gazetteer of the Hong Kong Region.” 1983. Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong. ISBN -962-209-043-5

If you would like to read it yourself or just take a look, it’s on the web in several places, including Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/851/851-h/851-h.htm

Pilgrim’s Progress is also on the web in several places and in several forms. Again starting with Project Gutenberg:

There are print versions: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/131

There are audio versions: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/21171

For several centuries this was a classic and a standard work on Protestant theology. Therefore, there were attempts to rewrite it for specific audiences. For instance, here we have a children’s version from 1909 : https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/39452

And someone around 1884 decided that it would a good idea to rewrite the work using nothing but words of one syllable (there was a series of such books and I proudly own Gulliver’s Travels in words of one syllable) : https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7088

But as for me, I gave up and simply accepted an invite from a grad school colleague, a wonderful woman from Uganda who had done work for the United Nations in multiple warzones (RIP, now gone due to Covid), to attend a Cornell Graduate Student Christian Fellowship meeting and watched the movie.

What I remember most, was a young looking woman with a Spanish accent who afterward commented “But why did he work so hard to find the truth and the path to Heaven? All you have to do is accept Christ and believe and then you can go to Heaven.” And with that I realized one reason why the spiritual paths of my ancestors are fading away and the current Right Wing Fundamentalist Christianity is taking hold far and wide in the USA today. —It’s instant! It’s convenient! All you need to do is spend the time it takes to just add water or put something in the microwave and soon salvation is promised and all questions answered! It’s perfect for the modern American psyche.

The “li” ( 里 ) is a traditional unit of measurement sometimes called “the Chinese mile.” Unfortunately, it’s exact length varied from place to place and era to era. According to Wikipedia of 12/07/2024, oh, how I hate citing Wikipedia, during the Qing Dynasty when the book was written a li was about 535 meters to 645 meters. Today the PRC Government has standardized the li as 500 meters exactly but they prefer that people simply use the metric system instead.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_(unit)

To find the volume of a “dou” I consulted the Wikipedia page for “koku,” a Japanese unit of rice as well googling the word “dou” as a unit of rice measurement. This led to several antique dealers who were selling or had sold Qing Dynasty Chinese measuring containers that were exactly one “dou” in size. All sources said that a Qing dynasty “dou” was equivalent to just a hair over 10.35 liters in volume.