Mass Chinese conflict in California in the 1850s, part 2 of a series on the early "tong wars" of the California Gold Rush -who, exactly, was fighting anyway?

Identifying the combatants

Greetings,

This is the second in a series in which I dig into two early conflicts among the Chinese gold miners in California. These were widely labelled as “tong wars” and often portrayed as puzzling with many popular histories claiming the motivations of the combatants as impossible to determine. I am discovering that they were not “tong wars” at all, but something distinctly different and much more understandable when placed in the proper historical context.

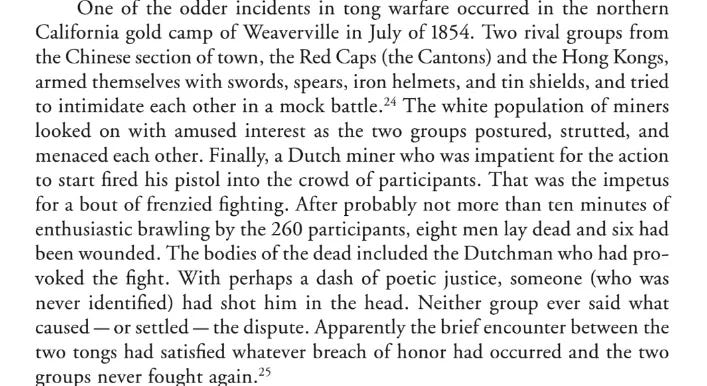

A photo of the Weaverville Joss House, a traditional Chinese temple located in Weaverville, California. Now a California State Historic Site, it was also site of a conflict among Chinese miners in the area that took place in 1854. Weapons from that conflict, widely mislabelled as a “tong war” or “the first tong war in California” can be seen at the Joss House museum. I visited there once when I was 12 years old and saw the”tong war” exhibts in the museum.

Last week I wrote about an outbreak of violence reportedly involving over a thousand people that occurred in the year 1856 in the town of Chinese Camp in California. In that same piece, I alluded to a second outbreak of violence of roughly the same size that occurred in the town of Weaverville, California in 1854. This week will partialy focus on the earlier, 1854 incident, but what I really hope to do is dig deeper and provide context.

Having spent time over the last week or so digging into these two incidents, incidents that were connected in motivation and identities of the combatants, I have to say the historical reporting on them is generally awful.

My goal over the next few weeks, and, sadly, I think it may be an achievable goal, is to produce a better and more complete picture of what happened in these two incidents, along with a description of who did it and why, than has ever been produced before. Of course, if it turns out I have missed some well done historical reporting that was done before me, then simply learning that it exists and finding out who researched and wrote properly about these incidents would also be a very good thing indeed

SO WHAT’S WRONG WITH WHAT IS OUT THERE?

Both of these conflicts reportedly involved large, opposing groups of Chinese miners that had publicly announced they were planning to fight each other, publicly commissioned the local blacksmith to make them swords, spears, and other weapons, and then publicly purchased them. When the pre-announced time came, in both cases the two groups faced off, while most of the non-Chinese, primarily White residents of the town and the nearby area came out to watch. When the fighting started, it tended to be short and loud with a relatively small number of casualties, little strategy or tactics, and then one side ran away.

Last week, I also shared a lot of descriptions of the 1856 event. These varied in quality and since some contradicted each other, we can assume they also varied in accuracy. Most were not first hand but came much later, often generations later, so some inaccuracy would be expected. None seemed to be written by professional historians, which does not mean they were inherently flawed. One thing though that most of these reports have in common, one glaring, gaping problem, is that they do not really explain who these people were or why they were fighting. Some make references to the participants being members of “Tongs,” but they still don’t explain what a tong is, at least not in any depth, and they never get into why exactly two such organizations decided to meet and fight.

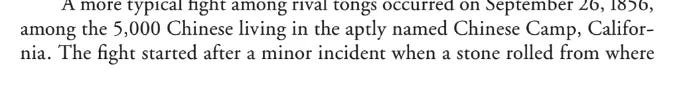

There’s often no hints of motivation. In fact, check out this description of the 1854 Weaverville “tong” war from pages 91-92 of a book called “Alcohol and Opium in the Old West: Use, Abuse, and Influence,” by Jeremy Agnew, copyright 2014, published by the McFarland Company. 1 Agnew is a prolific author whose books are often about aspects of life and society in the Old American West. Here’s his description of these two events:

Sadly, this sort of reporting on these events is common. In fact, I offered several on the 1856 incident last week.

Looking at the report above we can see that the author claims that nobody ever found out why these people fought. According to the author, you see, they never told anyone. Their motivations for the fight were . . . entirely . . . completely . . . 100% . . . for lack of better word “inscrutable.” Oh my!

And despite the fact that 260 adult men were facing off with weapons after announcing they planned to fight each other, it was, of course, a “mock battle” until “provoked” by a White guy, a Dutchman. “Sparked off” I might accept. -provoked, no way.

No. No. No! I will not use the “R-word.” Once that starts it never stops, at least not for a long, long time, and while its use continues nobody looks at anything rationally or analytically. However, like many people who have written about these incidents, the author who was not Chinese or Asian American, has completely minimized the actions and motivations of the participants.

As for his statement that the two groups never spoke of why they did this, it is complete nonsense. Both groups spoke of why they did this. At least one side wrote letters to the primarilly White readership of the English language, regional newspapers and told them exactly why they had been fighting. I plan to publish it in full either next week or the week after.

Three prominent members of the Sam Yip Company (not a “tong” -more below) took the time to write a letter in English to a regional newspaper, explaining exactly why their side and the other side had fought, and why, as the letter is clear to explain, their side was being quite reasonable and it was the other side, the one who they had opposed and fought with, who were the bad guys and quite unreasonable. The letter ran in the Shasta Courier on August 12, 1854, and I took the time to paste it in full in an upcoming issue. Stay tuned. Same Bat-channel.

In the 1856 incident, the Sam Yip company went so far as to write their threats against the opposing side, the Yong Wo company, and these were also published in a regional English speaking newspaper. I shared this clipping and its source last week.

Hmmm, it seems that the Sam Yip Company was putting a lot of effort into these conflicts. More on that later, but obviously to understand why they were so motivated about these things, it is probably a good idea to learn who they were and still are, as the group still exists. Again, more in an upcoming issue.

(BTW, why no Chonese characters on “Sam Yip Company” and “Yong Wo Company”? Because I want to spend time in a future issue getting into who exactly these people were and what the organizations were and their history. It’s coming.)

Here’s how the same author describes the 1856 conflict in Chinee Camp, California:

As you can see the author describes the fight as starting “after a minor incident” and then growing from there. And when it was over, the two sides forgot about the whole thing. In other words, they were, again, fighting it seems for no reason at all.

Um . . . yeah . . . inscrutable at best, childish at worst. As the hip, young left wing, socially ever so racially conscious, pseudo-intellectuals like to say “He OTHERED them, big time.” Oh my. . . Um . . . oh my. No comment.

So we have a problem in many of these reports where the actions of these people do not really make much sense. The authors do not seem to be describing the behaviors of rational adults. Few of these authors have taken the time to dig deep enough to try to explain why they were fighting or why they were.

Or even worse, when some of these reports do try to explain why in one case over a reported thousand Chinese gathered and in another over 200 reportedly gathered to fight each other, made a public display that they were going to fight, making it clear that this was not an accident but a very intentional incident, and then did so, the explanation that some of the Whites offered were nonsensical and clearly made their Chinese neighbors appear a bit childish. For instance, over a thousand Chinese planned to meet and fight one day and invested a great deal of money in purchasing weapons because, as one writer wrote . . . um . . . bored, local White drunks egged them on and enccouraged them to do so??? (this was in one of the accounts shared last week. It came from a regional travelogue written in the 1950s,) Um . . . um . . . well . . . Oh my!

And so it goes.

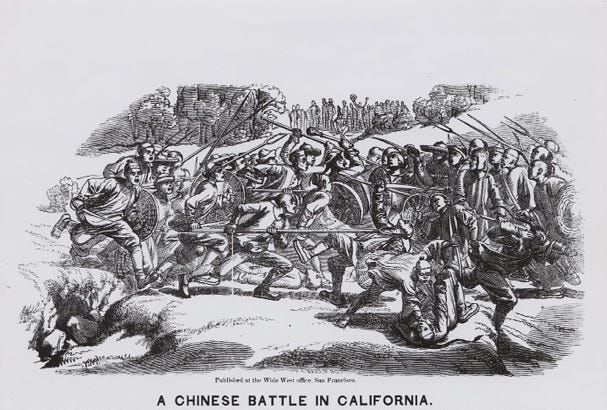

At least someone, somewhere drew a picture of the fight in Weaverville. (So far, I have been unable to track down where exactly this widely distributed illustration first came from.)

A period illustration of the 1854 conflict among Chinese miners in Weaverville, California

WHO WERE THESE GROUPS?

First, they were not “tongs.” While the popular histories often refer to these groups as “tongs” and the events as “tong wars,” none of the groups that were fighting were actually “tongs.”

WHAT IS A TONG?

First, pardon me if I do not footnote this section. Years ago, I wrote a book called “Tongs, Gangs, and Triads; Chinese Crime Groups in North America” and own about a shelf of books on the subject of tongs and related groups, I like to think I know enough about the subject to coast through this. I mean Wikipedia cites me on this subject and if you can’t trust the reliability of Wikipedia, well, who can you trust? Honestly, and I mean this, if you wish to know sources, please ask. If you catch me in a mistake, I will be grateful and admit it. Honestly, I enjoy the attention so ask if you wish.

First, the word “tong” in English generally refers to a Chinese sworn brotherhood whose members have taken an oath of loyalty to one another during an elaborate ritual. The name comes from a Chinese word for group or political party and is written with the following character “ 黨 “ (traditional Chinese ) or “ 党 “ ( simplified Chinese ) which is pronounced something like “tang” in Mandarin as in “Kuo Min Tang” ( 國民黨 ), the Nationalist party of the Republic of China, or as “tong” in Cantonese, the dialect spoken by most, but not all, of the 19th Century Chinese in America.

Most tongs are modelled on the same basic pattern, a pattern that arose in the mid-18th C AD as a mutual aid group, although according to the popular history that the groups promote about themselves, they claim to have arisen about a century earlier as an underground political group created by patriotic, outlaw Shaolin monks intent on overthrowing the foreign, Manchu Qing Dynasty and restoring the native, Chinese Ming Dynasty.

Often the different groups were known as branches of the “Tian Di Hui” or “Heaven and Earth Society” ( 天地會 ).

Their rituals and symbology and so on are surprisingly well documented, in part because British Colonial officials in places like Hong Kong and Malaysia took a strong interest in these organizations. Not only were they seen, justifiably, as a threat to public order and stability, but as many of these colonial officials were Freemasons, some imagined that there might be a prehistoric link of some kind between the Chinese Tongs and the Western Freemasons as both were sworn brotherhoods with elaborate rituals and internal secrets. In some cases, 19th century British colonial officials speculated that both societies, the tongs and the Freemasons, might have shared roots with an earlier, prehistoric society, perhaps in Atlantis or elsewhere although this idea was disproven, along with the evidence for the existence of Atlantis long ago.

If you have heard of the “triads,” the Chinese crime groups often associated with Hong Kong, they are the same type of organization and follow the same structure.

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, it was not uncommon for different tongs in San Francisco, New York City, and other major urban areas to fight each other.

The tongs still exist and if you can recognize the Chinese characters for their names, you can go to a large, old Chinatown such as is seen in several major urban centers in the US or Canada and spot large buildings that are the tong headquarters. Sometimes they even have English language signs

See! Here’s a photo of the Hop Sing Tong in San Francisco.

If you want the source of this amazing photo and what some would presume would be secret, clandestine, hard to get information on the location of what is often said to be one of the oldest Chinese criminal secret societies in all of North America, it came from Trip Advisor. See: Trip Advisor -Hop Sing Tong in San Francisco Despite the listing I am pretty certain that you can’t go inside and that they don’t give tours. If you learn otherwise, please tell me.

Are they still involved in crime? It depends who you ask. Probably, but they deny it. In the 1990s when I wrote my book, there was a great deal of concern that the tongs were forming alliances with the newer Chinese street gangs, and that Chinese crime groups would menace the free world after the Chinese take over of Hong Kong in 1997 and the exodus of high level gangsters from that city. In hindsight, there was a bit of the classsic “yellow peril” sensationalism in a lot of writing on that subject at the time (By the way, I don't mean to say Chinese crime groups don't exist or that they are full of nice people who are merely misunderstood and that they don’t do predatory things. I mean I have written here about the alleged activities of Alice Guo and the Chinese syndicate run scam centers that force human trafficking victims to scam and cheat and steal from people, but most of their predatory activities, I hate to say it, are aimed at other Chinese, particularly the undocumented workers who make up a sizeable chunk of the US and Canadian restaurant and massage parlor staff.)

BUT WERE THESE GROUPS FIGHTING IN CALIFORNIA IN THE 1850S ACTUALLY TONGS?

Um . . .

No. They weren’t.

Well, then, Peter, what were they?

Thanks for asking. I am dying to tell you.

They were a different kind of Chinese organization called a “Huiguan” or in English they were referred to as “companies.” In mid-nineteenth century USA, the most important Chinese organizations were the “Chinese companies.”

According to tte wikipedia entry on the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association:

These immigrant organizations were rooted in the Chinese tradition of huiguan (traditional Chinese: 會館; simplified Chinese: 会馆; pinyin: huìguǎn; [Mandarin] Jyutping: wui6gun2 [Cantonese] ),[11] viz., support groups for merchants and workers originating from a given area.

These were based largely on the region that a person came from and were headed by the more educated, more wealthy Chinese and Chinese American merchants who came to the USA.

In time six of these became recognized as particularly important and became known as “the Six Companies.” Ultimately, they formed a strong alliance and formed the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the unoffical but traditionally quite important “government” of most older American and Canadian Chinatowns.

The organization still exists and is still a significant organization in the neighorhoods where it has branches.

I hope to write more on the history of this organization and its component companies in the next few weeks.

Just as a point of interest, when I lived in Boston, I used to study Hung Gar Kung Fu for a few months at the Boston CCBA headquarters in Boston Chinatown. It was a nice place with an atmosphere similiar to a YMCA or the local Jewish Community Center with lots of activities like a Ping Pong league for seniors, arts and crafts classes for children, Chinese language classes for all ages, and, yes, occasionally martial arts classes in the evening upstairs. The class was small, friendly, about half White and half Chinese or Chinese American with much Cantonese spoken in the classroom, and I have no doubt other races would have been welcome. It was not a large class, and it’s coincidental that they weren’t there. While I did not stick with that art, although I do study other martial arts, I did enjoy the people and miss attending the classes there.

If you would like, you find all the branches in North America listd here: Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association branches in North America

At this time, during the first ten years of the California Gold Rush, some of the different companies that ultimately formed into the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Organization, the unofficial, historical government of American and Canadian Chinatowns, were openly engaged in violence against each other, and fought openly in mass conflicts on at least two occasions. — Which is fascinating and little known.

So now we know roughly WHO WAS FIGHTING. More details will help fill in some gaps, but the next big question is WHY?

I find this fascinating and have never seen it in print before. Oh, it could be out there, but it’s most certainly not widely shared if it has been.

In an upcoming issue, I will be digging deeper, offering more context and more details on what happened in Weaverville, California in 1854.

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SCR18540729.2.2&dliv=none&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SCR18540812.2.2&dliv=none&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------